Near the end of The Nothing Factory, the film’s ostensible lead player Ze (José Smith Vargas) angrily remarks to Daniele (real-life documentarian Daniele Incalcaterra) that he’s simply exploiting him and his fellow doomed factory workers so he can simply have something to “show his cinema buddies in France.” Ze seems to realize himself as a subject eternally linked to film, with the ins and outs of the proletariat having been a ripe topic since the beginnings of cinema with Workers Leaving the Factory of course, or extending into the neorealist films of the ’40s and then morphing into a reliable stream of documentaries and small dramas that turn up on the festival circuit.

What The Nothing Factory seems adept to answer through that earlier exchange is the question if social change can actually be achieved through film at this point in 2017. After all, it seems the working class has become a cinematic subject with an increasingly narrow audience, again only for the film festival folks in Europe. The subjects under the microscope are the workers of a Portuguese factory who one night are alerted that the machines from their place of work have begun to vanish, and it doesn’t take them long to realize their jobs aren’t long for the world either. Their particularly amusing if cruel predicament means they’re unable to actually seize the means of production. The only option for attempting a strike of sorts is to simply wait around the factory with no work to actually do, with the occasional roughhousing to make up the day.

The film comes as another entry in the age of austerity hangover, like Miguel Gomes’ Arabian Nights trilogy from a couple years back. Also like Gomes’ work, the film presents a director stand-in trying to wrangle reality into compelling fiction with the aforementioned Daniele, playing a riff on either Pedro Pinho (making his narrative feature debut) or simply a variation on Incalcaterra himself. Yet the director figure not willing to entirely commit to leftist ideals, or really an overriding aesthetic for his film within the film makes up simply a small portion of the film, much of it actually following Ze, an easy entry point for the audience due to his relative youth, decent looks, and family life.

Daniele’s indecision results in a song and dance number featuring the workers almost two and a half hours in — which has made the film misleading receive a “musical” genre tag on IMDb — and seems to hint at a somewhat more interesting film that could’ve been. If anything, it could’ve stood to be a more genuine mutation of forms. Admirably choosing empathy for its non-actor, real-life factory worker subjects over the ironies of cinematic representation for the majority of its lengthy runtime, The Nothing Factory still doesn’t seem to offer any real astute observations at the end of the day. The film’s good intentions and strong conceptual bent can really only go so far, as maybe you’ll realize this particular writer is looking to find a polite way to say that while quite sympathetic to theme of futility in the face of neoliberalism, which *ahem* can be certainly said to be more important than ever, he kind of got the entire point of the film about 45 minutes into its three hours.

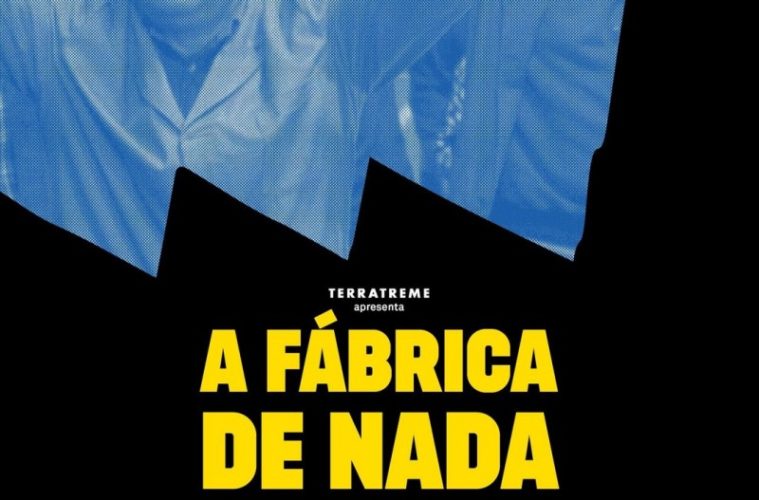

The Nothing Factory screened at the Toronto International Film Festival.