“We are so excited to have you here and are blown away this is even happening,” I signed off on a hasty call to Coop Vidéo de Montréal, setting up an interview with Robert Morin, a French-Canadian director who had taken on mythic proportions to myself and co-programmer Sean Price Williams. Coop is the illustrious production company Robert Morin established in the late ’70s to spearhead the production of his unique, beyond-characterization catalogue of films.

Morin, 74, has directed 15 feature films (that I know of) and over 50 shorts, all of which have stunning power and humor and trace the journeys of outsiders who revel in their own independence.

A fierce defender of individuality and pure expression, Morin remains a staunch representative of his Quebecois heritage, one of those artists that eschew all attempts of categorization as “not enough” or “too meager.” This is a man so capable of expressing his identity on film that a want to corner him or throw him into any logical career synopsis is, as with all great artists, a waste of time.

The films contained in this interview and the series are truly something to behold. “Edgy” is a poor descriptor of a catalogue that goes so many unreachable places. A group of junkies in Whoever Dies, Dies in Pain are holed up in a hostage situation with one shot police officer, with real, actual addicts coming in and out of the camera frame shooting up and philosophizing about existence.

A group of possible criminals wander through the placid dullness of a Quebec suburb in May God Bless America as they try to unravel a serial killer’s plot to kill them. All the while September 11, 2001 is happening in the background.

Or a profound, affectionate portrait of Jeannot in Morin’s first feature Scale Model Sadness, where a young man with Down’s Syndrome struggles to break out of his claustrophobic suburban existence through newfound love. The films of Robert Morin probe our interior lives with expert precision and empathy.

As Sean Price Williams and I began to descend through his massive film catalogue in preparation for the “QUEBEC-CORE” series, an 11-film deep dive into Quebecois Cinema starting this Friday at Anthology Film Archives, we found ourselves in perpetual awe of this new, true cinematic hero. How could a figure of so much power and sageness––capable of producing nightmares and deep humor in the same precise moment––not hit our radar?

We spoke to him on a calm Saturday morning as Morin, as he described, called from “deep in the woods” of Quebec, where he has just wrapped two new films, and was preparing to travel to Anthology.

Sean Price Williams: This is really an unbelievable, dream-come-true thing that’s happening. And it’s a real honor to be able to speak to you and show your movies. I know how this sounds, you know… but it’s meant really, very sincerely. Yeah: you’ve blown our minds this past year.

Robert Morin: Yeah.

SPW: And we’ve barely seen enough of your films. We’ve got much more of your films to see still.

Yeah, I’ll send you my two latest, and there’s one coming out this next week. As a matter of fact, I’ll send you the link for my last two nightmares.

[All Laugh]

SPW: Honestly, the purpose of the series is just to show some of your movies and I would love it if, at some point, we could do a real retrospective anthology of more of your stuff. Luke and I had a hard time narrowing it down to just a few to play. We’ve loved everything we’ve seen.

Okay, I’ll send you a couple more. I don’t know how much you’ve seen. All you got was from the Coop, I suppose.

SPW: A lot of stuff from Elephant and then some bootlegs. We were pirates a little bit, too. Do you have any more of the DVD box sets from Videographé? They’re all sold-out.

I’m not distributing those. I mean, maybe I can find one, yeah. I’ll try to get Videographé and I’ll send it to you from the video. They’re mostly shorts, so there’s a few features––very early stuff. Yeah, this compilation is really early work. It’s only mostly short short films, you know, 20-minute films.

SPW: Yeah. And you were making this kind of in a collective, like a film collective?

It’s Videographé that has made a collection of those.

The Mysterious Paul / Le Mystérieux Paul (1983)

Luke Rathborne: We were able to get your short The Mysterious Paul from Videographé and that we love. We didn’t have the translation at first, but it was pretty obvious what was going on. [It’s a short documentary, directed with Lorraine Dufour, about an aged circus performer who refuses to give up knife-swallowing.] It was one of those situations when, once we got the subtitles for it, we’re like, “Oh, this is exactly what I thought was going on.” They want you to stop putting an electric heated iron down your throat. The family is concerned. You keep putting a welding iron down your throat.

[Laughs]

SPW: Yeah, we want to watch all the other shorts and get subtitles. There’s so much more for us to see. I’m very excited.

When I come to New York I’ll bring a collection of those. Cool.

SPW: When are you coming to New York? Do we know yet?

I’m coming over on the 17th of April.

SPW: Excellent.

Robert Morin: So I can bring that collection over there with me. The collection is about 15-to-20 films.

LR: Unbelievable.

So “The Mysterious Paul” is among those, but there’s a few others that you might not have seen.

SPW: We have a lot of work, still, to do but we want to show more and more of your work and see more. That’s the point, I guess. And I’m gonna say a lot of nice things about you in front of you when we have an audience. I know Luke and I really just can’t believe that this is happening and we can’t say enough. Thank you.

It’s flattering. Thanks for that. And my ego is going be better this afternoon.

May God Bless America (2006)

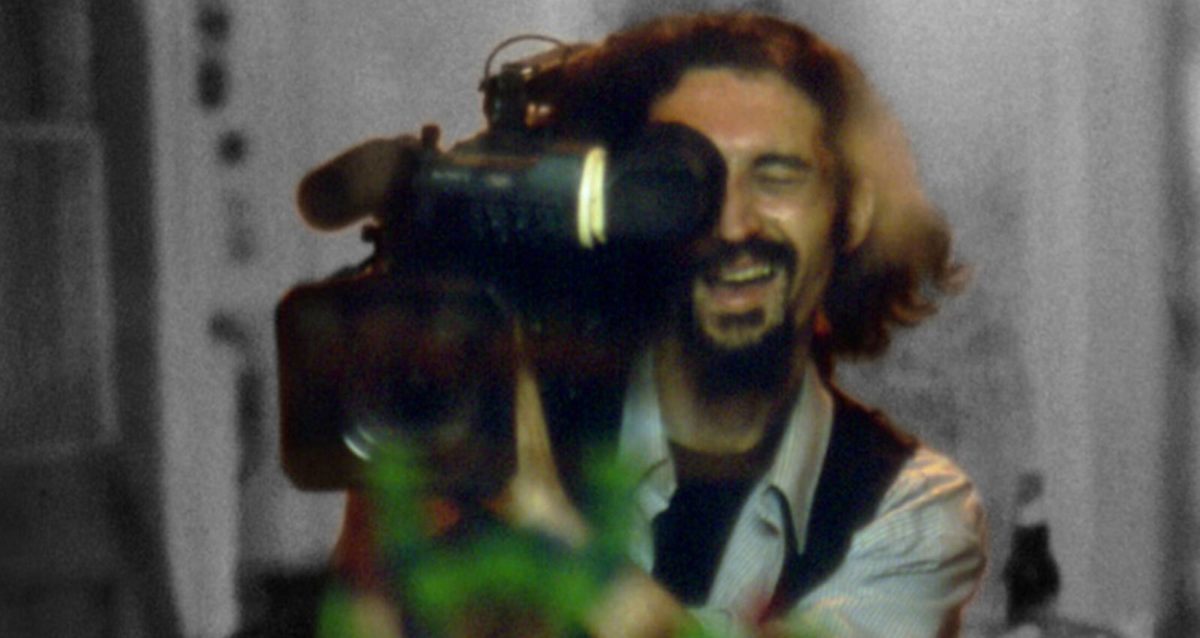

SPW: You did a lot of work. I have the May God Bless America DVD which has a documentary, the making-of. That is so great and you’re so cool in it. And I want to show that also, but it’s not subtitled, but it’s still fun to watch even without subtitles. So I think I might try to.

We had a lot of fun doing it, too.

SPW: It really looks like it. And the movie is so incredible. Absolutely one-of-a-kind, and then to see how much fun you guys were having making it is… yeah, inspirational. It’s all very inspirational.

LR: Yeah, when Sean and I saw these bubbles pop up when the characters were speaking to each other on the phone. Yeah, that was one of the first things where we’re just like, “We have to watch this movie.”

May God Bless America (2006)

SPW: I remember trying to show how people talk on phones and make it interesting cinematically. This is one of the most original concepts for me. So we’re big fans, and I’m going to make sure that Anthology Film Archives… they’re a rag-tag sort. They do the best they can with what they have. I want to make sure that you’re taken care of.

So far so good. I’ve been there personally, a couple of times, you know, decades ago.

SPW: Well, it hasn’t changed. [Laughs] Yeah, they, they keep threatening a renovation but they don’t do it. I’m happy about that.

Who’s the boss now?

SPW: I think it’s John Mhiripiri. It’s a kind of a committee. I know Jonas’ daughter, Una, is kind of involved.

Yeah. How long [since he passed?] I mean, the two brothers are long-gone. Yeah?

SPW: Jonas died about five years ago. But yeah: there are a bunch of enthusiastic guys. This is our first time programming. I’m a filmmaker. Luke’s a musician. So we’re new to this.

Where can we hear or listen to or watch your films and music?

SPW: I directed a movie that just came out called The Sweet East. I think it opened in Montreal maybe a month ago. I’ve done cinematography for a lot of movies but it’s all small movies because I’m non-union. I can send you a link for sure.

LR: I’ll send you some music, too. I did want to ask you a few things about a couple of movies that we’re showing. Sean and I were really shocked by, in a great way, Whoever Dies, Dies in Pain– the mixture of real and artificial. Real actual addicts mixed in with actors portraying ones, in a fictional police-hostage situation with a fake documentary crew.

Whoever Dies, Dies in Pain (1998)

I was really inspired by neorealism and cinema Italia. So a lot of those films are directly inspired from that style, approach, and concept. And I just came back from Rome and I shot a little film over there with Africans who survived crossing the Mediterranean. Nouveau fiction, kind of fiction / documentary. But the last two films are silent. You won’t have any problems watching. There’s no language.

SPW: Great, the best. I used to work for Albert Maysles, the documentary filmmaker. I don’t know if you ever met him in New York. He was kind of my mentor. I guess I come from documentary, but I really love when the best films are when the documentary and the fiction become very unclear.

No, there’s no real documentary in a way. It’s always very subjective.

SPW: Yes. So I think that’s the future and that’s how your movies are very futuristic.

[Laughs] Well, I’m still striving to do more. But it’s hard to get money and funding, especially when you’re old. [Laughs] There’s a wave of political correctiveness in Canada and the money is pretty much politicized.

SPW: Robert, your films are very politically incorrect and I think we love this, and I think that you’re going to see in New York––people are really going love this. I mean, the films are very, very edgy.

We’re really anxious to be there.

LR: We were really fascinated by May God Bless America. Some of your descriptions of it and its relation to a kind of naïveté on America’s part towards international relations. Like this idea that you can ignore a problem for so long until it appears in front of you. And it’s kind of created out of a sense of arrogance of the country itself.

The idea is exactly what you describe. I mean, it’s like a reality that you ignore for a while and then they pop up in front of you. It was true with 9/11 for you people, but these suburbs [of Quebec] are like that too, and that’s where the two meet and also the indifference. If you’re not American––I mean, if you’re from Canada––9/11 here was just like a little TV show, in a way.

LR: Yeah. No, it’s unreal the way, in the film––in the pawn shop––it’s just playing on a tiny TV in the corner and there’s maybe a moment’s glance over to it. They are occupied with everything else in their lives. But nobody in the film would call it a 9/11 film. But it’s a completely different take on this idea of what that means––it’s just fascinating to me that it’s like the characters are almost satirical of the United States.

You know, they’re so caught up with themselves and nothing is important for them.

May God Bless America (2006)

LR: I don’t know if this was the correct translation, but in the translation you described it like there’s almost an autism towards the way the U.S. deals with these foreign countries. Like, we suck out the resources and have kind of no concern for how we’re damaging the framework of the society around it.

Well, yeah. No, the problem of the United States, in general, is like this echo chamber the people live in. I mean, that’s why I was very surprised you’re having me shown in New York. [Laughs]

Petit Pow! Pow! Noël (2005)

LR: Yeah. I think that there is an openness to talk about these things. We tried to get Petit Pow! Pow! Noël, but I guess the rights are trickier for that one. There’s something with the rights of it being for TV.

It’s a film I paid for myself so it can’t be… I don’t know that we’re gonna show it in the network. We’re gonna show it one of these days.

SPW: There’s no question. It’s very powerful.

It was never shown on TV, obviously.

LR: Oh, okay.

SPW: That was one of the first ones we saw and it really blew our minds.

It’s a film that I shot with my real father.

SPW: So that is your real father.

Yeah, and that’s me. I mean, the other, the crazy guy––that’s me.

SPW: I’ll make a remake of your film. I’ll give you the money, by the way.

[Laughs] You’ll have all rights to do it. And for me it was a great help. I mean, it’s the only thing I ever did with my father in my entire life and it was just about time because he had cancer and he was going.

LR: Do you feel protective of that film in terms of explaining what is artificial and what isn’t? When we watched it, by the time we saw the credits rolling we thought, “Okay, so there was crew on this.” You know, there was planning, it becomes obvious to you when you think back about it, but when you’re experiencing it, it seems important that it feels almost like documentary.

Well, that’s the idea––was you to do those like documentary. I did a couple of those and this one; maybe the last one that I really did was with my father. But obviously in a hospital like that you can’t shoot anywhere or film the personnel, so I had to bring people in to do tasks and sub roles. And so, yeah: it was like a documentary too on those. We call them CHPC here, the places where they’re stuck. It’s a place where you die. And my father was there, too. There’s a part of my biography in it too. Some of the reproaches of this guy are mine, were mine towards this guy, and it was pretty much that [the father character] was not very present all his life. So yeah: some of it, half of it was true and the other half is complete, complete fiction. Obviously trying to kill him wasn’t real.

SPW: [Laughs] Okay, so you’re a great actor. That was clear.

LR: Yeah. We considered you a great actor. We thought that it was probably set up in voiceover or something like that.

SPW: No, it’s true. You watch it very carefully because the whole time you’re… it’s the strongest film and it’s like you really don’t know what’s real, what’s not. And so you’re paying so much attention to what’s happening, what you’re saying, where and when things are being said. It’s very brilliant.

And it was really written. It was not improvised. Every scene I had written the monologue before, so I could time the shots.

LR: And so you’re really saying the monologue there, on-site?

Yeah, but I was listening to them. I pre-recorded them on a tape recorder and I played them during the shots so I could concentrate on the camera work and the rhythm and he could sign at the right moment and, you know––

SPW: So he could hear these things that you were saying?

Oh, yeah, of course. [Laughs] We had this complicity. The film was shot in this period of six months. So a little bit here, a little bit there. We try, we do it. We don’t like it. We shoot again. So yeah: my father was pretty aware that he was playing a role also.

SPW: Wow.

LR: And were there special effects at certain points?

SPW: We were wondering about the needle in the leg.

Yeah, we used homemade special effects––like you were guessing.

LR: Even the fact that we have to ask you, shows that you did a very good job because you’re seeing the camera go up and down from that shot. And we were sitting there debating, “Well, there could have been like something being squirted or something like that.“

Yeah. In the swish pan, we put the needle in the skin––well, not in the skin, but on the tape and it was just a rig. All the special effects are mechanical, like the steam and then when he is being cleaned like a car. It was sufficient. I paid for it out of my own pocket. I’m very surprised that you get the information that it is protected by TV rights.

SPW: I mean, we might be wrong.

LR: No, I was just talking to someone at Coop and they were just saying, “I have to figure out how, maybe they were just trying to get the copy or something like that.” But we were trying to squeeze in as many films as we could. And then we saw May God Bless America. And we’re like, “Okay, we’ll revisit Petit Pow! Pow! Noël and we’ll be able to program that eventually.”

SPW: Like I said: we want do a whole thing on just your films.

Scale Model Sadness (1987)

LR: The first film, for which we have the title translated to Scale Model Sadness, I know we’re really excited to show that because it’s my understanding that it was your first narrative film?

Yeah, it was my first feature-length.

SPW: And that was the first one that we watched too.

LR: It’s a really beautiful movie and Robert, when we send that around to people, it just kind of got this life of its own where all of a sudden different friends are coming up and talking to me about this movie and that’s how you can tell when something really has a power to it. It almost gets this “folk” quality to it where everyone just starts passing it around.

No, that’s great because it’s the only way my film has been distributed so far. [Laughs] I mean, most of those films have never gone very far. In terms of TV or screenings, they’re all pretty weird for the so-called “industries.” So there’s a lot of people showing, passing the films around with different means. Like it started on VHS, now it’s on DVD, and also on the web.

Scale Model Sadness (1987)

LR: In keeping with what Sean was saying, though, about a lot of these films being predictive of concepts in the future, it seems like only now is the film industry even a little bit coming around to the idea of, “Why not cast a disabled person in the lead of your film?” It’s like we’re still not even there. But it’s just becoming a discussion, now, to portray disability by somebody who is actually disabled, you know?

Yeah. But the tendency is there… I mean, what’s the name of that kind of documentary-type feature done by these people living in trailers in the southern states?

LR: Vernon, Florida?

Done by a woman. What’s her name? No, there are people living in their cars, basically, and some of the actors on that film were real people but they were not especially bizarre people.

LR: Oh, was it Nomadland?

Yeah, Nomadland. Yeah, some of the people that are playing in it are for real.

LR: Yeah, for sure.

SPW: And the press was all over that. They were saying, “Oh, my gosh, what a new concept of having a big actor and then also real people.” I mean, come on… [Laughs]

The Italians were doing that right after the war.

SPW: Absolutely.

That’s how I got my first kick in cinema. Vittorio De Sica, Rossellini. Most of their films, especially the De Sica––all his first films were people picked up on the street, and The Bicycle Thief is a masterpiece in this sense.

SPW: Not a lot of humor in those films. But you know, at least you bring some humor.

[Laughs] No, no… yeah. [Laughs] Yeah, I hope so.

SPW: We need that these days. We appreciate that.

LR: Yeah, I mean, even in these films at the darkest moments, Sean and I would look over at each other and just break out laughing sometimes, because the way that you’re handling the material does have that black humor interlaced.

SPW: Well, and we discovered that with so many of these Quebecois films. That this very, very particular brand of humor that we really did not and do not see in other movies presents itself. It’s really like a whole world of stuff and it’s just how unknown it is here, in a way.

Yeah. On the contrary, most of the American movies, the tone is changing in those films. You go from comedy to drama; some American filmmakers are like that. I mean, the Coen brothers: sometimes they touch that kind of shift between comedy and drama.

SPW: Well, they’re from Minnesota––almost Canada. [Laughs]

Yeah, then there you go.

Quebec-Core, including the films of Robert Morin, takes place April 5-19 at Anthology Film Archives.