Without a doubt, The Act of Killing is one of the most affecting documentaries you’re likely to ever encounter. Filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer has captured the essence of evil and the truth can be quite unsettling. These are human beings; they have lives outside of their terrible actions and many of them even have adoring families and friends. How do we, as an audience, come to terms with the fact of someone being repentant in the face of their terrible past?

In this eye-opening documentary centering on the mass killings in Indonesia during the mid-60s, we focus on the gangsters that perpetrated the terrible crimes and how they live now. Shortly after seeing the film at SXSW earlier this year, I sat down with Oppenheimer to discuss the way he shot the film, his own journey with the various gangsters, how long he was with them, and why gray characters are hard to find in cinema and even documentaries today. As a warning, there are spoilers for some reveals in the film, but one can see the entire conversation below.

Can you talk about all the anonymous names in the credits?

Yeah, I mean it’s an Indonesian crew and we’re filming the film mostly in North Sumatra, but we’re filming with national, political, the vice president of the country, the head of the paramilitary movement and it’s unsafe to have their names in the film. There are some places in the film where their faces get in the film and we digitally alter the faces. It’s only fleeting so it’s not that difficult to put another face just for a few frames, but we were careful. You see a sound person, which you do see a couple times in the film, their face has been changed.

One of the things I noticed is that you capture a lot of conversations that don’t seem to be directed towards the cameras. Were you obvious about the fact that you were recording those conversations?

Oh, of course, of course.

Why does it seem like they’re OK with it? Were they just not quite understanding the fact that they were on camera?

No, no. They’ve been filmed continuously for years with me, and I would show the footage back to them. I think you’ll have to understand what they thought they were doing and what I told them, which was pretty much the truth — that they’ve done something of historical importance: they killed one of the biggest killings in history. Their whole society is based on it, their whole lives have been changed by it; it had a major impact on the history of the Cold War. To understand how they feel about it, I want to film them making scenes and film how they discuss it, how they plan it, what they think they should film, what they shouldn’t film, and show the scenes uses; let them film the scenes themselves and use both. So they knew that part of the process was to film their making of, their planning, their reactions to what they filmed, their doubts; that was actually the method that I pitched to them.

One of the most interesting things about Herman is he runs for an elected office position and he’s reluctant to give anything to his constituents , even though he knew that was part of the game. You tell in the story that he eventually lost that election, he didn’t get, and it just seems so weird that he had been riding high on this gangster mentality but he didn’t want to play along.

I think he didn’t have the money, to be honest. I think that he’s not that well off, he’s not poor, but I mean it’s very expensive to bribe, to give. Voting areas are 100,000 people and [if] you have to give everyone $10, that’s $1,000,000. He didn’t have it. I think he simply didn’t have the money. There’s actually a longer, kind of director’s cut of the film, and there’s a great line where his friend is like, “I could’ve helped him, what an idiot, he doesn’t have any money. Even rich candidates can’t get elected, how’s he going to get elected?” So I don’t think that he’s trying not to participate. I think what’s really important about the campaign is that Herman is so honest; because he’s so honest about how the whole system works and he’s telling us that he’s planning (if he gets elected) to use it as an opportunity to make more money by going in and extorting Chinese people in the markets.

In narrative films there is not a lot of gray, but you’ve given us a real-life gray character in Anwar Congo. It’s weird to elicit these kinds of reactions from an audience member, because you can see them and you can feel the intensity in the screening when he’s talking about how bad he feels about this stuff, and you start feeling bad for him. All of a sudden you’re like, “wait, but he did all of these bad things — why am I feeling bad for him?” Are you feeling a lot of that intensity and a lot of that emotion while you’re filming this or does it take a little while to separate yourself?

No, I think that. Well, first of all, I’d say that the whole tradition of cinema, you’re right, is the same. It’s movies about good guys versus bad guys, but good guys and bad guys only exist in stories. In reality, every act of evil in human history is perpetuated by human beings like us and we actually have very few movies about how we commit evil, why we commit evil really, and the effects of evil actions on ourselves and our societies. If we care to really prevent these things from ever happening again, which we say, the mantra following the Holocaust, or not the mantra, pbut] I grew up with this sort of slogan “Never again.” “Never again” is far too often interpreted to mean “Never again to us.”

We think we’re the good guys, but there are bad guys out there and we may have to eliminate them one day. But actually if we really mean “Never again, we’re not going to destroy other human beings in massive numbers ever again,” we have to take seriously the reality of what happens, which is human beings destroy other human beings and then there are no black and white characters as you said. I think the problem with our tradition of human rights documentaries is that we film; we go into these overwhelming, messy, political situations and we simplify them and usually we simplify them by saying, “OK, we’re going to make a movie. This is totally messy and overwhelming and I don’t dare let myself as a filmmaker be tainted; and the audience has to have an easier, digestible experience about this film because I’m trying to give them a simple, political message. So I will make the film about the victims. They’ll be presented as good guys; the audience will have the comfortable position of identifying with good guys and therefore feel good about themselves and look at the bad guys”.

But that’s actually not the way the world works. That’s not what exists in the world, that’s technique for creating a tidy experience. But if we neaten up the world so much in our story telling that we don’t see what the world is, then we have no chance of learning from history and actually learning from what we do to each other so that we can be better prepared to prevent these things from happening again. I think I came into this, as I said at the screening, as though I’d been entrusted with a mission to expose what happened on behalf of survivors and the human rights community working with them. So of course I saw the perpetrators at first as kind of incarnations of evil, “I’m going to meet the killers.” How “oooo,” you know? What I went looking for was monsters, but what I found were human beings. So I also went through the same terrible, uncomfortable realization. Even in the last scene where Anwar is choking on the roof, that was indeed the last scene I filmed with him. And the moment that he’s choking on the roof, I remembered — and] by that time I’d been filming with him for years, we were close, I care for him — you can say maybe I don’t like him but I love him and vice versa. If you see someone you love suffering, what do you want to do? You want to put the camera down and you want to go and put your arm on him and say, “It’s going to be OK.” That’s your instinct, right, if you want to console somebody; but I knew in that moment I can’t do that.

You have to capture it.

No, yeah, but it wasn’t even that. Before that, there was a sense, “yes, I have to bear witness,” but before I even thought of my duty as a filmmaker, it was more, “If I put it in there it won’t be true.” That was as much as, if I go and put my arm around him and told him “It’s going to be OK.” I thought, “But it’s not going to be OK,” and he knows that. It wasn’t that I was afraid to say something dishonest on camera. Before I thought of that, before that such a thought would cross my mind, I thought, “Oh, fuck, it’s not going to be OK, there’s no way of consoling him because he has done this and it’s destroyed him. And his body is realizing that now and he’s really destroyed.”

When you bring a film to a festival, do you have to sell it a certain way? Do you have to pitch it a certain way or are you able to take this movie and just say, “Look, this is going to be challenging.” Are you even a part of that process?

I think different audiences have different levels of resistance to a film like this. We in the United States — I’m an American — like to think of ourselves as world’s good guys, who are out on our white horse with our white hat protecting peace and hypocrisy. Even the liberals in the country, and the left of the country who are critical of that, we like to think, “Oh we’re right. We’re being critical.” So we somehow in our sense of self in the United States, even when we blame ourselves, even though the ones on the left say, “America is the biggest imperial power,” we feel self-righteous when we make those criticisms. So Americans, we’re good at self-righteousness, I think. It was very interesting presenting the film in Berlin because in Berlin they’ve been identifying with perpetrators for the last 50 years, 30 years, 40 years, since they started really dealing with what happened with the Holocaust. It was like there was no resistance to the movie at all. No one laughed, which is a pity because there are laughs in the movie. You put laughs in editing, you put them and they’re there for a purpose. Everyone was just embracing the movie; we won the Audience Award at the Berlin Film Festival. I never thought such a dark film could win an Audience Award. I would be quite amazed.

Yeah, especially in that area.

So I think every festival, every audience, has a different relationship to the film. But I think the film touches enough people that it’s basically at the word of mouth about this being a very powerful and unique film that’s different from anything else anybody’s ever seen. [That] is what really sells the film.

You’re taking it from the bad guy’s perspective and humanizing them and showing that these are humans that are capable of doing these things. I think it’s much more important to show that side of it, because we can realize that human beings did this, not monsters.

Yeah, that’s the truth. Hitler didn’t have scales and fangs, or green skin; he was a person.

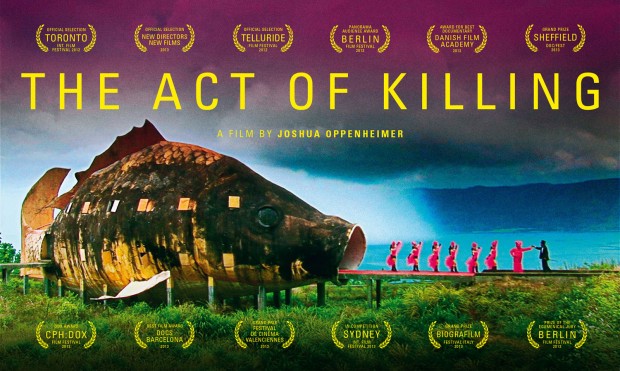

The Act of Killing is now in limited release.