The release of Douglas Sirk’s magisterial melodrama All That Heaven Allows on Criterion’s Blu-ray line is something to celebrate. Few filmmakers used the Technicolor palette as intensely as Sirk, and the bold colors of his films deserve the kind of transfer that Criterion’s restoration process brings to their best work. But there’s something even more exciting buried in their package: a restoration of Mark Rappaport‘s exquisite documentary, Rock Hudson’s Home Movies.

The subject of the film is, needless to say, Rock Hudson, the iconic actor who serves as Jane Wyman’s co-star in the Sirk picture. Having died of AIDS complications in 1985 — an event which brought public attention to his homosexuality — Rappaport’s essay film is, in many ways, an attempt to show the true tragedy of Hudson: an actor who was forced into an image of hypermasculinity while only ironically revealing his true identity through these films. Rock Hudson’s Home Movies is still one of the most ingenious video essays ever assembled, using a barrage of now-standard techniques to examine the private life of a man through his public persona, in addition to deconstructing Hollywood’s own codes and conventions.

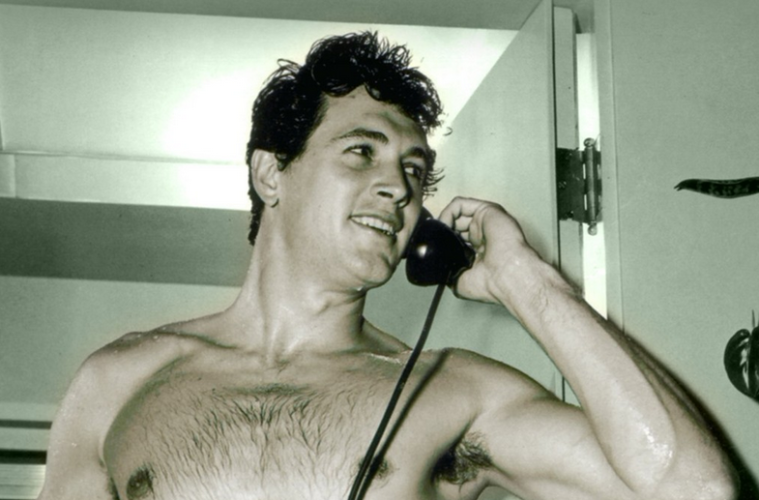

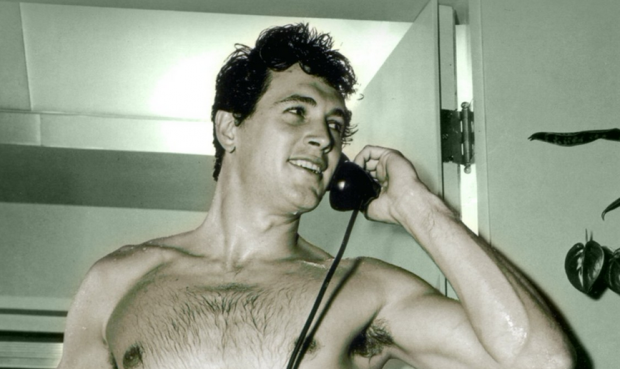

Lasting a brief 63 minutes, Rappaport’s film is told via an actor (Eric Farr) playing a persona of Hudson from beyond the grave while VHS clips of his films play in the background. (One may lament that Criterion and / or Rappaport did not use better restorations for the often-shoddy VHS rips, it is all-too-suited for this underground film meant for private viewing; as Rappaport’s notes on the film explain, Home Movies needed the invention of VHS to exist.) Farr’s Hudson asks, “Who can look at my movies the same way ever again?” Rappaport’s selection of clips are what, now, ring as incredibly obvious moments: Doris Day asking Hudson in Lover Come Back why he’s in another man’s apartment; a clip of Hudson and Tony Randall comically sharing a bed; and Hudson’s anxiety over marriage, as pressured by an older, naked man taking an awfully keen interest in him. And, of course, there’s his role in Howard Hawks’s oddball comedy, Man’s Favorite Sport?, where Hudson plays a supposed fishing expert who, secretly, has never fished in his life, and must fake it through the film.

“It’s not like it wasn’t up there on screen, if you watched carefully,” explains the stand-in, who leers at the camera with a witty smirk, calmly asking that we examine these films without ever condescending to them. Farr and Hudson become unified (the former’s costumes are various mimics of outfits worn throughout the latter’s films), at one point even appearing to grab each other’s shoulders. It’s less a gimmick than a way to present the movie star with honesty; Farr almost acts with an amusing disposition, but it’s also one that brings out the honesty of his own voice — almost as if he’s saying, “This is who I was. There’s no point in hiding it.”

A weaker version of the film might see Rappaport do little more than create some bland supercut of amusing lines and moments underlining Hudson’s transparent orientation, offering little more. Thankfully, Rappaport lays out a cunning argument through Farr and his voiceover. This iteration constantly examines the provided sequences — male bonding, fear of women, the awkward kisses — and attempts to find the ideology of the 1950s and 1960s within. It is less that Hudson was the only the star doing these types of scenes, for coded sexuality was extremely common — one need only think of Cherry Valance and Matthew Garth‘s “gun contest” in Red River or the “oysters” scene in Spartacus. But what Rappaport points out is that these scenes always came with a price: one could hint at a real identity as long as it remained on the screen, subsumed into heteronormative culture by the time credits rolled.

It is thus that Rock Hudson’s Home Movies is less an essay than an elegy and a call that perhaps an innocent time was not so innocent. These scenes not only take on a comic edge through their come-ons and gay panic, but also that scenes of Hudson’s various deaths become strange predictions for a man who would die of what was still, then, a disease linked to queerness. As if staying true to the idea of “change mummified” of Andre Bazin’s ontology of cinema, his body is dead, but his screen persona is trapped on the celluloid images. Hudson’s infection becomes the secret of his life, the disease that he must carry deep within him — and, as Rapaport notes, ironic, given how often he played doctors in his films.

Rappaport was not the first to re-create a star through a found-footage movie — he acknowledges avant-garde artists such as Joseph Cornell and Bruce Conner as influences — but Rock Hudson’s Home Movies simply did more with it, and, in expanding the role of this technique through the use of VHS, incidentally paved the way for every supercut from the last decade. It’s a monumental work of cinema, and one which certainly deserves more time than simply being viewed as a “bonus feature.”

All That Heaven Allows and Rock Hudson’s Home Movies are now available from Criterion.