Due to the nature of the relationship between these films, spoilers follow for L’Avventura and Clouds of Sils Maria.

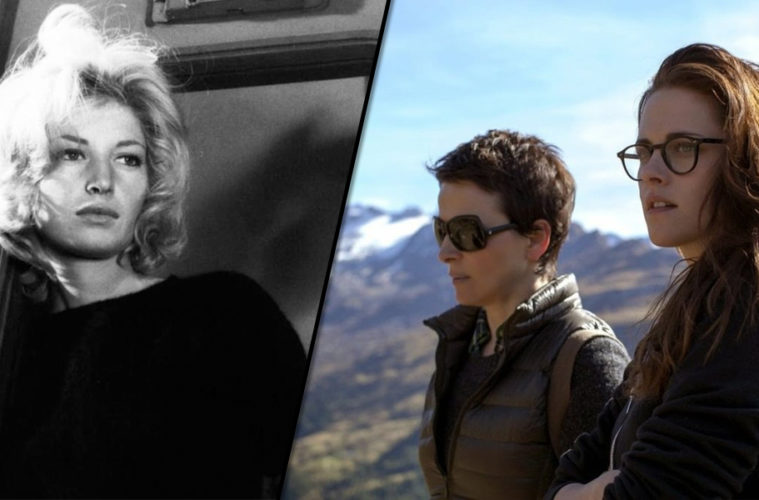

“Cinema needed that scene to exist, this thing to be affirmed.” This is how Olivier Assayas describes cinema’s great non-moment: the disappearance of Anna in L’Avventura, Michelangelo Antonioni’s deservedly canonical breakthrough. Now out in a pristine 4K transfer for its Criterion Blu-ray debut, L’Avventura continues to seduce, confound, and haunt in its still-atypical, dream-like depiction of the lost souls of Europe. As part of their masterful re-release, Criterion has reworked a 25-minute, 2004 interview with Assayas as he gives the film a terrific close reading. Assayas’ comments are not only insightful in his describing Antonioni’s effort, but they also ring true for his recent picture, Clouds of Sils Maria: the idea of absences turning into metaphors.

Many have deemed L’Avventura’s notorious plotting as an unapproachable object, but it is lucidly alive from the film’s opening moments. Two best friends — upper-class stifled Anna and her best friend Claudia (Monica Vitti) — go out to an island with the former’s fiancé and family. We know things are wrong for Anna, and, as Assayas points out, her impulsive decision to jump in what had been described as shark-infested waters already signals a death drive. Assayas asserts that what makes L’Avventura special is how it so naturally flows into the mystery, suddenly deriving us of any narrative tension. In this break, Assayas exclaims that we must search the images for a new story as the characters search for their own place in this alien world. “What will replace the presence of meaning?”

This simple, modernist twist is not enough to make a film, just in the way that Kristin Stewart’s disappearance in Clouds of Sils Maria is meaningless without the final 20 minutes of Juliette Binoche contemplating her new role without her id-like opposite. Even less so than Antonioni does in L’Avventura, Assayas plays a major character’s disappearance as completely metaphoric — no one discusses it as something we can confirm physically happened. And there is only one hint of where the film might be heading: when Stewart’s Valentine spins out in a rock-fueled driving binge, as if her existence is literally tied to Maria — her own jump into the water.

The search for Anna seems to be the “plot” of L’Avventura, but as Assayas notes, the wild goose chase is overwhelmingly baffling, most notably in the scene where the two soon-to-be-lovers search an abandoned town. What becomes thrilling for Assayas is how this sequence ends: after making love, Sandro and Claudia drive off, and the camera suddenly appears to be surveying them from a dark alley, slowly pushing in as if spying. Though Antonioni’s mise-en-scène is often seen as being extremely modernist, Assayas notes how classical most it can be — perhaps relying less on dialogue, but never obfuscating the frame, where the camera’s presence simply envelops the actors in shot-reverse shot structures. Except in this moment, however, which he calls the “Zero Point,” which is what truly transforms L’Avventura and announces the film’s true intention: the constant fear of what we cannot see or know. It concludes with a shot of an empty church, recalling Bergman’s Winter Light, and Assayas notes how this place of worship has been abandoned, thus representing, for him, a loss of faith in these characters.

Assayas does not find L’Avventura befuddling and hard to understand, but simply demonstrating a type of ambiguity that leads us toward something classical. He slowly walks through the film’s ending, where Claudia wakes up (as from a dream) and notes that her lover is missing, just as Anna had been before. This time, however, she finds the lost one — in the hands of another woman. What was profoundly mystifying before thus becomes beautifully troubling: a fear of being replaced, of losing what one has. Assayas tracks Antonioni’s final shots, as the two disjointed lovers “reuinite” ambiguously in front of a stone wall, noting how this has become something truly honest in a way the original dramaturgy between Sandro and Anna could never be. This final reunion is not metaphysical, but truly human.

Assayas’s film has a similar rhythm between the metaphoric and the human. In staging Binoche and Stewart together, he allows the actresses to retain their more natural performance styles — Binoche more profoundly gestural and didactic, Stewart more minimal, rejecting sudden movement. This isn’t a fault, however, for the script they rehearse and discuss reflects this pointed difference, and it’s no accident that Maria performs her stage directions while Valentine simply speaks them aloud. Assayas’ films have often been built on a rush of energy that suddenly peters out, be it Carlos’ glamorous terrorist-turned-unwanted ward or Something in the Air’s sexy radicalism becoming the tedium of daily life. Sils Maria doesn’t just bring him closer to Antonioni territory by employing these performance styles, but even by using the landscape of the Swiss Alps as a key environmental flow that directs his languid pace, just as L’Avventura contrasts the utter silence of the North with the crashing rocks of the South.

Assayas’ description of L’Avventura is not particularly unique, especially considering how often the film is written about. But it does reveal the way he thinks about cinema, and how films can both hide and reveal meaning to create “a documentary on the loss of meaning.” As a former critic for Cahiers du cinéma (a not-uncommon credit for contemporary French directors), Assayas’ clear articulations don’t show how L’Avventura may be a direct influence correlation to his films, but instead represent a kind of stylistic Rosetta Stone for understanding what he does with his shots. And for many filmmakers of his and Antonioni’s time, attempting to escape the atom bomb of influence that is L’Avventura proves impossible. As Assayas says, “It seems obvious or simple, but at the same time, it’s a moment that, from every point of view, is almost historically a turning point in the evolution of film.”

L’Avventura is now available on Criterion and Clouds of Sils Maria will be released on March 27, 2015.