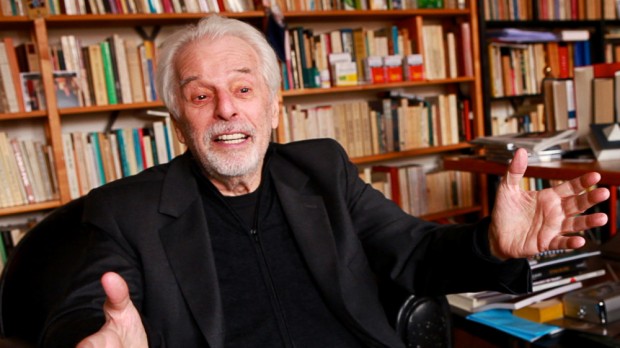

For a documentary on a filmmaker I had heard of but had never seen any films by, I was a bit hesitant going in, but I absolutely adored Jodorowsky’s Dune, which is hitting limited theaters today. Whether you’re a Dune lover, a fan of his films, or have no interest in either, this documentary is a must-see. Inspiring, touching, moving, and all-together entertaining, the film owes a huge debt to the man in the middle, Alejandro Jodorowsky or as he’s lovingly called, simply Jodo, and it’s clear that director Frank Pavich embraces that completely here.

The film is about Jodorowsky’s enormous vision and grand scope for the failed adaptation of Dune, the legendary science fiction novel by Frank Herbert. While that’s the initial hook, you stay for the wonderful character of Jodo and to see how hard he strove to create a vision worth experiencing. More than anything, this is about art and what drives us to follow our passions in live. Jodo lived by the sword and died by it too — he was relentless in getting his vision on the screen and enlisted that biggest stars, both in front of and behind the camera, to help bring his ideas to life.

Last year I had the wonderful opportunity to sit down with Pavich to discuss any and all things about the film. Along the way we talked about when he realized the gem he was sitting on, finding the perfect ending to his film, how he went about animating the storyboards and his goals for that and the music, the first time Jodo saw the film, how he got a hold of all the material throughout, and more. I believe our conversation adds to the film and what it achieves, so check it out below in full.

The Film Stage: When you’re trying to edit this documentary together, do you know you have this kind of gem?

Frank Pavich: No.

At what point did you realize you were sitting on something?

I always knew we had a special story, but we didn’t know how it was going to be received, if it was going to be well-loved. I mean, who knew? We really didn’t know until our premiere, and our premiere was at Cannes this past May. At our premiere screening, not only was our audience in hysterics and laughing throughout — totally behind Jodo, which was great — but they actually broke into spontaneous applause at four different points of the film, at the end of a certain story. Once that happened the first time, we were blown away. None of us expected such a thing like that. That just proved to us how behind Jodo the audience could be. It was really up until then that we were nervous. Maybe it was going to be crickets? But that really set the ball rolling. Every screening we’ve had since has been miraculous. People just fall in love with him. We thought it would be a fun film and it would be good because we were inspired, but we didn’t know the audience would feel the same way. The bar is set very high by Jodorowsky and his vision, and his outlook on life in general. As he says in the film, “Why, why do anything if you don’t have huge ambition?” Why? There’s no point. It’s difficult to do anything, so go all the way. You have to try. And if you fail, it’s not important. It’s not about the end result of the product. It’s about the process along the way and it is whatever you make out of it.

Here’s where I’m coming to this film from: I’ve heard of Jodorowsky and I’ve heard of his vision for Dune before, but I’ll be honest. I’ve never seen any of his films. So coming from that perspective, you fill in the gaps incredibly well. I feel like I’ve been given a crash course on Jodorowsky.

Here’s where I’m coming to this film from: I’ve heard of Jodorowsky and I’ve heard of his vision for Dune before, but I’ll be honest. I’ve never seen any of his films. So coming from that perspective, you fill in the gaps incredibly well. I feel like I’ve been given a crash course on Jodorowsky.

Excellent. Great.

I know to seek out El Topo and The Holy Mountain.

That’s great because we were hoping to make it…

Accessible?

Accessible. Yeah. Hopefully the documentary is not only for fans of Jodorowsky or fans of Dune or science fiction. Hopefully it’s for everybody. I kind of use my wife as a barometer. She didn’t know Jodorowsky. I don’t think she’s ever seen a science fiction film and she’s never heard of Dune, and she’s brutally honest. But she was really enthralled. She fell in love with him. He’s such an amazing storyteller. So hopefully it holds up. Hopefully we put in enough information and background. To us, the ideal audience is the blind viewer. The person that goes in and has no clue and no history of any of this. Then they come out and are inspired to learn more and see more Jodorowsky. Maybe even see the David Lynch version of Dune. Who knows?

Maybe not.

[Both laugh]

So he was with you at Cannes. Did he see the film for the first time there?

He did. Yeah. He couldn’t make our premiere screening but he was there for the second one. He was sitting with his wife next to me and the whole time I’m watching the two of them out of the corner of my eye and they were enthralled throughout. And at the end, I can see they’re both wiping tears from their eyes. So I leaned over and asked, “So, what did you think?” And he simply says to me, “It’s perfect.” That was one of the greatest moments of my life. Because here was this man who gave us this gift of this amazing, personal story of his. I mean, who am I? I’ve no right to contact this man and walk into his apartment and pitch my idea for a documentary. I’m not Errol Morris. I don’t have this track record, but he’s a reader of people. He’s a reader of intentions. I think he saw that I was obviously enthusiastic, as I am today for him, and that I had a real respect for him and a gratitude that he was going to let me tell this story and do it right. That I would take my time in creating it. That it wouldn’t be a DVD featurette. It wouldn’t be a depressing story, “Oh, look what could’ve been.” It’s something more than that. The film is about him trying to make Dune, but it is about so much more than that — those overriding themes of ambition and it’s interesting to make a story about a quote unquote failed project, but for the documentary to be so inspiring, enlightening, and funny.

It runs the whole gamut.

Yeah. You know you have the audience when they’re laughing, applauding, and when he pulls out that money during one point in the film, and he goes, “What the hell?”. You could hear a pin drop in every screening at that moment. I guess it’s a good sign because I still watch it. Every time it screens at a festival they’re always like, “Do you want to watch it?” and I’m like, “Yeah! Sure!” I must have watched it who knows how many times during the festivals, let alone the editing room. I never get tired of it.

When you set out to make a documentary, a big goal is to create a narrative. But that’s pretty difficult to do without heavily steering a conversation.

Right.

One thing you do phenomenally well here is you take the character of the Prince Paul Atreides in Dune, who is played by Jodo’s son, Brontis, and you have this story throughout the documentary and Dune itself of the Prince dying and his aura going and spreading out all over the place.

Yes! Yes!

And you have this line in the film from him.

Isn’t that the killer line?

When you heard that, you had to have said, “Oh, shit, I’ve got a movie now.”

Yeah. That was part of our last interview. We knew we needed something else. I really wanted to get the two of them together because these two people need to be together. They both have influenced each other’s lives. It really needs to be Jodo and Brontis. So we sat with them for quite a while and we were going through all this stuff. We had a couple of ideas we were thinking. Like, I knew that that last scene of Jodo’s film. That scene 90, the death and resurrection of Paul, really tied into the theme of our story. That the film dies but it has spread out. I knew that was going to tie together but I didn’t know how we were going to do that. And yeah, it just kind of happened. Even at that point, when Brontis gave that line and Jodo was like, “OK, good, you go it? We’re good!” He starts taking off his microphone. And I was just like, “Yeah, I guess we do have it.” Why continue further? But yeah, Brontis just nails it. Oh, it’s so fantastic.

You get some of these outside perspectives for the film. Clearly, though, you hitch your horse to Jodorowsky and you showcase him throughout. But you have interviews with Magma. But not Pink Floyd. Not Mick Jagger. Why not?

We thought about trying to contact Pink Floyd but it’s kind of difficult. Because they all hate each other. Do you go to Roger Waters or do you go to David Gillmore? It became really complicated. But the Magma thing, well, everyone knows Pink Floyd. But not a lot of people know Magma, so it was kind of a cool thing to introduce people to them. But we also wanted to keep… I’m not a big fan of documentaries where it’s 90 minutes and there’s 110 voices. I can’t follow it and I lose interest in 10 minutes. I don’t know who is talking and I have no connection to anyone. I have to read everything. “Whoa, whoa, whoa, who is this person?” So we wanted a small number of people that you spend time with and you get to know. This should be an emotional connection. It can’t just be facts. I’m not trying to vomit facts out. There would be so much more that we could have included if we wanted to do that. We want that connection. I want people to go, “I love Brontis! I love Magma and I’m going to buy one of their records.” You want to spend time and hear their voice.

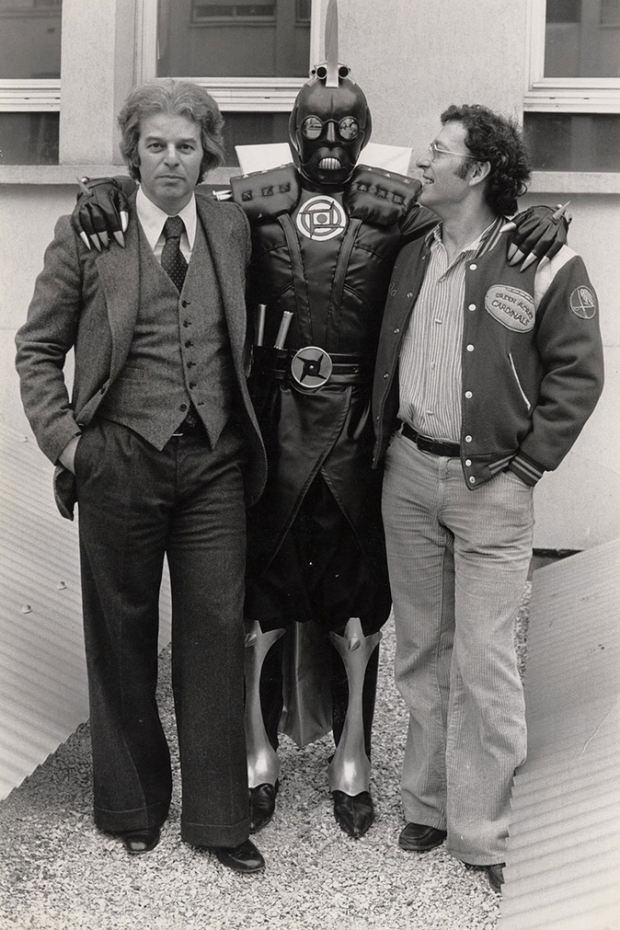

Jodo’s actual Dune project never went into full-blow production — nothing was ever shot and the film was never made. So what you’re dealing with is all concepts. You bring in some of the production designers and conceptual artists, which is perfect. But did you ever go after anyone for interviews and realize that they didn’t have anything to actually show for their involvement in the film? Like, that they would just be a talking head?

We were really particular about who we went after to talk to. So I didn’t even both going after a Mick Jagger or someone like that. If you can’t get the lead roles… I mean, David Carradine passed away, Orson Welles passed away, Salvador Dali passed away. “Oh, Mick Jagger‘s still alive, but he had a small role. Let’s go to him.” Then it becomes like stunt casting. And I don’t like those kinds of documentaries either. “Look at all the famous people we got.” What? Just because someone is famous means they have a lot to add to that story? Maybe Mick Jagger could have added to that story, but it would have felt lopsided. We have Brontis, who was going to be the star of the film, and that’s Jodo’s son, so that makes sense. It would just seem too peripheral almost. We wanted the film to be lean. I read some review that said the only problem with the film was that it didn’t show more animation and more of the artwork, but then he said that that probably means it was just the right amount. And I was thinking, “that’s a pretty good line.”

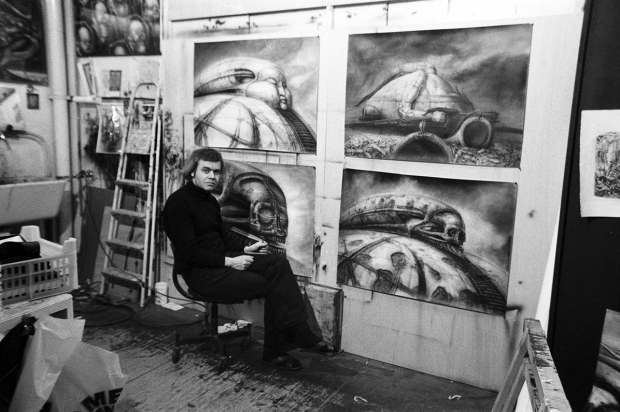

Speaking of the animatics, there’s this movement in the comic book world where they are creating these things called motion comics. They basically take the original, flat drawing of popular comic storylines and in Photoshop lift the characters off the page. They move them a bit and do rough animation to make their mouths move and things like that. But it’s never anything but the original drawings and words, but just brought to life. That seems literally exactly what you did with your animatics. What was that process like for you?

It’s a tough thing because you want to breathe just enough life into it without it being overwhelming. Maybe in the hands of somebody else it would have been too ostentatious. Too full blown. “WHOA! 3D!” And that’s not what Jodo is. You want to take these, for the most part, storyboards. The Mœbius storyboards, which were just pencil on paper. They were quickly drawn but with a lot of emotion and with the entire story, and take those and breathe just enough life into them where you see the movie and the scene come to life. But then your imagination takes you the rest of the way. You take the pencil and you just create a little life, you add a little bit of color, and sometimes there was original color in them, and then your mind fills in the rest.

What would this scene really be like? What would it be like with actors? So we have this animator who is based in Los Angeles named Syd Garon. He had that perfect touch for it. It was also trying to stay true to the time period as well. So, again, it’s not like ultra computerized. Just because you have the technology doesn’t mean you need to use it. You wanted to have that feel without going over board and screaming, “THIS IS 1974!”. It’s got to be right. Jodo’s work are timeless in many ways. They are from the 70’s but they are a different universe. They’re his universe. So we approached the animation and the music in the same way. Our composer, Kurt Stenzel, had never done anything before but he had that light touch to it. The music is of that era and of those instruments. But it’s not heavy handed.

Last question because I know I have to wrap with you, but I’ve heard first-hand accounts from some of these old movies back in the 70’s like Blade Runner where, when they were done filming, a lot of the props, the storyboards, and everything in between were literally trashed by the studios. They didn’t know what they had.

Oh, absolutely.

But with this film, considering it was never even made, it had to be even more so.

Sure, which is why there’s only a couple of those books left.

But that was Jodo’s copy in the film, right?

Yes.

How much did you have to pull directly from that book and how much material did you uncover that you couldn’t use because it was so deteriorated?

There was nothing deteriorated. Everything is actually fine. The book is in great condition. Michel Seydoux has another copy of the book. Those are the only two that we know for a fact exist. And then Michel Seydoux has the original storyboards. The original, 80 x 100 or 60 x 100 centimeter pages. Which is really what we scanned to get the highest resolution possible so we could animate it and go in and explore the texture of the paper and the pencils. But all that exists. It’s all sitting in his office in a cupboard. All locked away. Chris Foss has all his stuff. H.R. Geiger has all his stuff. It was real artwork created. It was treated as such by the people because they all knew it was a great creation. Whether the studio knew it or not, I don’t know. When you walk into Michel Seydoux’s Camera One production office in Paris, there are four or five original pieces of Dune artwork framed up on the wall. Every day, for the past 35-40 years, it’s been up there and he’s seen it every time he walks in. It’s in his daily field of vision. They all love it and see the importance of it.

Jodorowsky’s Dune is now in limited release.