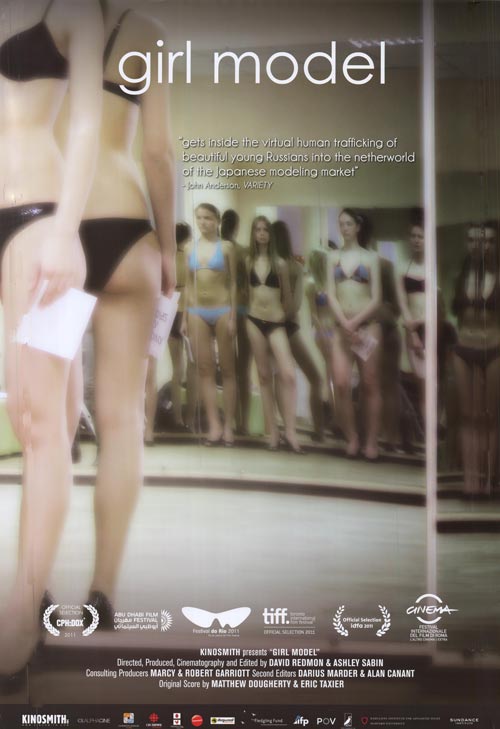

The work of David Redmon and Ashley Sabin first came on my radar when they arrived in Hartford, CT to promote their eye-opening documentary, Mardi Gras: Made in China, tracing both the production and disposal of Mardi Gras beads. Recently I chatted with Redmon regarding his latest documentary Girl Model, which he co-directed with Sabin and I reviewed at TIFF. Girl Model has screened at festivals internationally including the One World Human Rights International Documentary Festival and you can read our conversation from SXSW below as the film is now in theaters.

TFS: We met back in Hartford (at Real Art Ways) a few years ago and I was wondering what role cities with vibrant art communities that house these Micro Cinemas in often non-traditional venues (galleries, bars, libraries, coffee shops) play for you as filmmakers and distributors (via Carnavlesque Films)?

David Redmon: It’s even more necessary than before, and you had mentioned we were a distributor; we are no longer a distributor because we just can’t keep up with the game. We had to cut our distribution company; I guess liquidate is the business term. So we no longer release films and, in fact, just this week we signed a deal for Girl Model with First Run Features. I think micro cinemas like in Hartford and what Erik (Bowen, programmer of the Hartford International Film Festival and Kino Cafe) are doing is even more relevant because there is no way Ashley and I can get our films in Landmark Theaters, they aren’t going to play at the multiplex. Those kinds of cinemas create new norms of what cinema is, and Micro Cinemas show alternative forms of films and stories.

The reaction from TIFF seemed to very positive to Girl Model, I’m surprised to hear your not in a position to have it show at a few of the more commercial art houses nationally.

I would love to have our films screen at the multiplexes, but we’d also love them to screen at other venues, too.

I understand you also come from an anthropology background – I often view your work as about global products. Can you talk about this theme in your work?

It’s funny, we were having a conversation with a professor at UT about how we try to focus on a small items, like a Mardi Gras bead or a person that scouts girls in Russia. So we shot with these people or objects and items, and that brings us to multiple levels of interaction – a person brings us to culture, culture brings us to society, society brings us to a problem the individual exists inside both culture and the problem. Likewise, that person is likely linked to the commodity – the item and this is how our stories come full circle. An individual never exists alone, they’re part of ritual, society, and society is just filtered with contradictions. People that live within these contractions provide us with a more multi-dimensional picture rather than us trying reinforce our ideology or use film to espouse our own ideology. We don’t do that through our stories, we try to understand the stories of the people we’re documenting, and instead of reinforcing what we believe we try to focus on them.

There are very few moments in Girl Model where you interact with the subjects, either Nadia where you allow her to use your phone, or when you ask a scout directly about his business model. Otherwise it’s very restrained.

When to include our voice in a movie? Obviously we’re not Michael Moore or Morgan Spurlock, so we don’t go that far. In that situation (with Nadia), she’s on a cell phone, if we don’t include our voice – how did she get that cell phone, how does she know how to use it and what number to dial. If we didn’t include our voice that moment would have been met with suspicion, it can create unnecessary confusion. So we include our voice or let her reference us, so its clear that we’re side-by-side with her and helping her. There are other times we could have included our voices and we didn’t – another Born into Brothels wasn’t needed and I mean that statement in an artistic manner. Why repeat what’s already been done?

There are some filmmakers working in the same mode as you and Ashley, like Nina Davenport is someone who injects herself and voice into her films as a way of talking about her own discomfort with the subject she’s documenting. I noticed that a bit more with Mardi Gras Made in China.

Nina Davenport, I believe went to school at Harvard and studied with Ross McElwee and Robb Moss – so those are filmmakers who have no problem including themselves in the film and they do it extremely well. If you’ve seen The Tourist, an early film by Robb Moss, he and his wife are the characters and it works really well. So in that sense, Nina is trying to illustrate her own anxieties and conundrum with the characters, but I don’t think we go that far. We could have easily included our relationship with Ashley Arbaugh (the talent scout), which would have made the film more baffling. But we didn’t want to draw attention to ourselves, the story isn’t about us. What we try to do is remove ourselves as much as possible in the editing room, which is a false sense of objectivity. We’re acknowledging objectivity is impossible. So what we choose to put in the film is filtered through our own subjective choices and experiences while trying to maintain the point of view of the characters and their experiences.

The way we met Ashley Arbaugh is she actually sent us an e-mail, asking us if we wanted to meet with her. She told us that she’s a scout who finds girls to become models. She also said she had years of diary footage that she shot of herself as a model. And she was just wondering if there was a story there – and we said we don’t know – but let’s see if we can discover it together. We met up with her and we told her there is a story, but we think she’s the main character – and she put on this performance – “really, I’m that interesting” and we said yes, so that’s how the story started. But we didn’t put that in the story because that’s not what the film was about – Nina Davenport might include something like that. Maybe we made a mistake because I really like her films.

How about your relationship with Tigran (of Noah’s Models) – he said he views himself as the modern day Noah, giving girls a better life…

There is no relationship with Tigran, we know him through Ashley (Arbaugh) and the first time they met she told us to leave and we were baffled and disappointed. We returned and he was eager to speak with us. We were confused what Ashley told him, but he agreed to let us film him anyway. Later, we called Tigran and left a message on his cell phone. We told him we’re still making the movie and that we had a few questions, but we need to know more about his relationship to this industry – we left him a voice mail and he never called us back. He called Ashley (Arbaugh) back instead. She then called us and said “why are you calling Tigran, you don’t call Tigran, you go through me.” So Ashley my partner and I said “Fuck, we’re two years into the production of the movie, we’ve spent thousands and thousands of dollars – removing money from our bank account rapidly and the only way out was to get through the story,” so we had to listen to her and do it her way. We still don’t know what she told Tigran, who he is, or why she wanted us to film him.

I noticed your partner Ashley Sabin credits herself as A. Sabin, another place where you removed yourselves from the film to avoid a sense of confusion. Did you always intent for Ashley Arbaugh’s tapes, which are disturbing to see her go through this downfall moving from New England to Japan, to end up in the film?

My partner put A. Sabin in there because people were confused as to why Ashley the scout was making a film and who was doing the shooting, so my partner distinctively removed her name to separate herself from the character. The diary footage was given to us by Ashley the scout and she told us if it makes a better film use it, and we went through 12-14 hours of footage of and selected the most complex moment that show her as a person in a circumstance of transition. Here she is going into the modeling industry, she’s in a transitional moment of confusion and how is she going to get out of it? It’s pretty clear when you see the diary footage she transitions out of it by becoming a model scout.

How long did you work on the film – from the first meeting to TIFF?

Anywhere between four and a half to five years depending on your definition of production, we started shooting in 2007 in China; none of that footage was included in the footage.

Did it not make the cut?

It didn’t make the cut, but it wasn’t part of the story. When we met Ashley she told us she was also a designer and her idea was to film her making her clothing in a Chinese factory that manufactures clothing for Victoria’s Secret. So our idea is when we get out there, we would film the entire factory and the hundreds of workers who manufacture her products. Then she told us she was going to Russia to find girls to become models and these girls would be sent to Tokyo and Paris during Fashion Week to model her clothing. We thought early on that would be her story, so we’d flash back to her diary footage, so we could contrast her experience and the models she selects, and their experiences. For some – reason and you’d have to ask her – her clothing was never finished, there was no indication that she was having a show during Fashion Week, and when we got to Paris, we discovered she wanted us to meet a guy named Tigran. And we’re like “okay, fine” – we hooked up a microphone to Tigran and listened to what he said and that’s how we started this film.

It sounds like you were planning a different film than the one I saw last September at TIFF.

It sounds like you were planning a different film than the one I saw last September at TIFF.

Well actually it was a Ukrainian guy named Alex that she wanted us to meet, but he told us to get the heck out, and so then Ashley took us to meet Tigran. We hadn’t been to Russia yet, and so Tigran told Ashley that he has this modeling school in St. Petersburg, and then sometime later, Ashley ended up scouting these girls that Tigran had trained in these schools. And that’s how we met Tigran for a second time, in St. Petersburg Russia, but Ashley (Arbaugh) arranged everything.

The other strategy you employ is this crosscutting technique following Ashley Arbaugh’s travels, on Trans-Siberian trains with that of Nadia’s, the girl’s models experience in Japan. It’s very effective. It’s a really interesting and thought provoking film. Thanks for talking with me.

Thank you.

Girl Model is now in limited release.