Nick Hamm hasn’t directed a feature film since the 2004 failure Godsend, but he’s back this month with Killing Bono. To most, the title would suggest some kind of black comedy that offers up a bit of revisionist history, but the movie isn’t even about the world’s biggest rock star. Instead, we hear the little-known (and, at its heart, quite sad) story of Neil McCormick, his school friend who almost made it to the top. Almost.

In this interview, you’ll hear the filmmaker talk about some advice the band gave him, what he thinks of the film’s somewhat unconventional lead, and what it was like to direct Pete Postlethwaite in his final role.

The Film Stage: When you were working on this film, how much consulting were you granted by U2 — if there was any?

Nick Hamm: Well, that’s kind of a big question. It’s a good question, but it’s a big question. When you’re going to make a movie that has anything to do with somebody’s life rights — or you’re going to make a picture that involves one of the biggest bands on the planet — you have to have a relationship with them in some way. But it wasn’t a U2 film; it’s not about them in any sense of the word, other than when they were at school. And what they represent in the movie is a counter-point — their success represents a counter-point to Neil [McCormick‘s] failure.

But, having said that, we had very good relationships with the band, and they were incredibly gracious. And they were very supportive of the project; one of the producers on the film, Ian Flooks, was their agent for twenty years. So, on a personal level, I met with The Edge and I met with Paul McGuinness, who’s their manager — and both of them were very amusing and very funny about Neil. They gave us great material for their old artwork; you know, you can’t use their artwork unless they say it’s possible to use.

So the relationship with them was always very easy, but I didn’t require anything from them, and they knew the movie wasn’t about them. They knew I wasn’t going to do anything spiteful or bad to them. And when they eventually saw the picture, the whole band saw it together in Australia. They fell about laughing; I think mostly about the size of Adam‘s hairdo in the beginning of the movie. And I think they joshed each other for about three or four days about how ridiculous they all looked when they were sixteen or seventeen.

I thought it was interesting that you didn’t portray Bono as some villain because Neil’s success was somewhat offset by his own. With that said, how do you personally feel about Neil McCormick? Do you see him as a sympathetic guy, or do you think his constant mistakes make him a little pathetic?

I think the film is a celebration of failure — it’s a celebration and analysis of failure. And it’s particularly relevant to the film business or the theater business, or anything to do with the media. It’s about somebody whose dreams and ambitions far outweighed their talent, who let hubris and jealousy destroy the ability they might have had to make a proper career for themselves. And it speaks right into the heart of what a lot of people go through on a daily basis in the entertainment industry. It’s about the Gore Vidal line, “I die a little bit every time my friends succeed.” Which I’m paraphrasing.

And to go back to your question, in terms of the anti-hero — the character is an anti-hero. He’s an everyman. That’s why I wanted to do the picture. You know, normally music movies end with third act dramas in Madison Square Garden, thousands of screaming fans, signing ceremonies, and private jets to Hawaii, right? That’s the conventional third act structure of music films. Success is how you end the movie, right?

Yeah.

In this movie, failure is how you end. And you sort of know you’re going to have failure from the beginning of the movie, because you sort of know that U2 made it and they don’t, because you’ve never heard of them. Therefore, I think you look at the movie in a slightly colored lens. In the scene when Bono offers Neil and his band the chance to open for U2 in front of a massive crowd, when you watch that in a cinema of two-to-three hundred people, everybody drops their head and groans at that moment. [Laughs] And you sort of know, then, that the movie’s working on that level of, “Oh, don’t do that, don’t be an idiot.”

It’s nice that the movie shows things from a perspective that can be kind of hard to understand. When you were making the film, was there ever a desire to put a little more focus on U2, or would that have just been completely unnecessary?

I thought that was unnecessary, and I didn’t actually think that was going to be very interesting, because I wasn’t interested in any sort of exposé or story of “how U2 rose to power or got to fame.” I really wasn’t interested in that kind of movie; I wanted to tell a story about a guy who failed in the music business, rather than succeeded.

Failure is what happens to 99% of people. If you like, this is a movie for the 99%. [Laughs] Alright, that’s what happens to most of us: we don’t succeed. You know, we get by, we live, we function, we think, we do our thing, but we don’t become mega-stars.

What were your thoughts on recreating a period? Because there’s a scene where the characters go into a club and the song “You Spin Me Right Round” is playing —

Yeah, that’s a great song.

It’s funny, because I thought it was a little too obvious at first to use a really popular, well-known song like that, but then I realized that it’s the exact kind of song that would play at a club during this time, and the next song you use isn’t something that’s nearly as popular. So when constructing the film, was there a concern about what music to set scenes to? Specifically, were you worried about using songs that would seem a little too obvious?

Well, we really investigated — first of all, I grew up in this period, so I’m old enough to remember those songs; I remember being there, in those discotheques and those f-cking things at that time. I was twenty-something in the early ’80s, so I knew the period. Going back to the music question, we were forensic about the music in the film. From day one, we had to rewrite most of Neil‘s music and rerecord it and reproduce it, so we had to make a musical journey for him and his band, so that they could nearly be signed but not signed; so they would have a couple of hits but not… you know, you couldn’t give them covers.

But, also, that musical period was fantastically interesting. It was post-punk, it was romantic. Some of it was terrible crap, awful stuff — but some of it was really quite amusing and funny. So in the club scene that you’re mentioning, the “Round Round” song? That’s a very popular song; it also comes a bit heavily, and it comes down to money, what you can afford. You know, can you buy the rights on that song and not another one? So sometimes you’ll have a wish as a director for these songs, but you simply won’t be able to afford the licensing rights on them. You can have these, but you can’t have those. But we were really, really on it, about how we wanted to show the musical scene of that period.

The movie might garner some attention from the fact that it’s Pete Postlethwaite’s last film.

Pete, yeah.

Does it feel strange to know that you directed such a magnificent actor in his final role? If you had known that would be the case beforehand, would you have felt an extra sense of responsibility when directing him?

That’s a really interesting question. Number one, I was a friend of Pete‘s for thirty years, so we were mates, and we were in the theater together in the ’80s for the Royal Shakespeare Company. So we used to stay together, live together, we did plays together, and we were good friends; we knew each other very well. This was the first chance we had to work together on a picture, years and years later, and his work was amazing.

During the pre-production, he was originally going to play the gangster role in the movie. During the pre-production, he called me and told me he was ill, he had cancer, that he was going through chemo, and that he needed to sort things out — but that he’d still love to do the picture. In other words, that was about four months before the movie started. So he wanted the idea that he could, at some point, get through the chemo and go and act. But we couldn’t insure him to play the gangster role, because it was too… I don’t know, it was just too hard, physically, for him to get through the next three weeks, with the shooting schedule of that.

So we wrote that role for him, of the gay landlord, and we wrote that speech for him about fame. And when he gave that speech on set — the day he gave that speech on set — everyone sort of knew he was sort of by himself. There was a kind of hushed moment on set where everybody went, “Jesus, that’s an amazing man.” None of us knew, obviously, that he was going to pass away. It was a huge shock — I thought he was going to get better. He told me he was on chemo, he was going to get better; he was in remission. And then he just got worse.

Did you find a struggle in maintaining a certain tone? Because the movie can be very funny at times, but I also think it’s a very sad film, too, because of how this guy keeps failing.

[Laughs] Right.

Was there an issue balancing this man’s failures with the comedy of it, and how he couldn’t make worse decisions?

It was really hard to do that, actually; it was very hard to keep that balance, and sometimes I think I succeeded, and sometimes I think I didn’t. And so sometimes I think the sadness or the emotion diluted the comedy, and sometimes the dilution of the comedy affected that. But I wanted to do both. It was important to me that it was funny; you can’t do a story like this and not be funny. Anger is such a great source of humor, and resentment & failure is such a great source of comedy. That’s why I wanted to do the picture: Because I knew there would be great comic situations. Jealousy is just such a great thing to watch onscreen; you know, the fury and anger is fantastic, so that’s what fuels the comedy. But I also knew it was about a serious subject.

I mean, I could have gone much darker. I could have gone really dark, and it’s interesting when you listen to some people talk about it. Some want me to go darker, or some people want me to go lighter, or some, you know, they want it to be funnier and less sad. Or more sad and more dark, or more psychotic and more weird. But you could never really please anybody — you have to just sort of try and tell the story in an interesting way, in a way you think people might enjoy it.

This is your first theatrical film in about seven years, so what about this material made you really want to come back, and do you plan to jump back into that world anytime soon?

Yeah, I went back to London to build up a different business. I was producing stuff, and running an agency, and owning a business, and making different content in different areas. I sort of wanted a little gap from the theatrical world for a little while. But now, yeah, I’ve got plenty of energy to go back into it.

You know, the Godsend experience wasn’t a particularly joyful experience, so I didn’t really want to repeat that. I’d made lots of movies before that — independent films in London that worked really well — and with Hollywood, Godsend was my first experience here. So I wanted to go back, sort things out, build a business, do some television work, do some digital work, do some advertising, create a kind of proper culture around me, and then make another picture from a position of security. And now I feel fine, but you know as well as I do, Nick — you’re literally as good as your last bloody movie. [Laughs]

When you’re doing a film such as this one, do you think about the general public’s response because you’re partially dealing with such a famous subject? Are you worried about how fans of the band will view it?

I really am. You know, I’m not really concerned about fans; I think they love it because they get to see a side of U2, and there are certain aspects of the movie that are true. U2 did put the sign on the door of the school corridor to sign up for the band, and they did all rehearse for the first time in Larry‘s mom’s kitchen, and the drum kit didn’t fit in — it was too small. And they were terrible, and they couldn’t sing. Those things were authentic rock moments that I kind of wanted to make real, to get right. The rest of it was all fiction mixed with fact.

So I think for the fans, they get a kind of early insight into the genesis of the band. For the non-fans, because a lot of people don’t like U2, they can watch the movie without being whacked over the head by them. U2 represents everything that Neil wants; they could have been The Rolling Stones, they could have been R.E.M., they could have been The Who, right? They just had to be a band that had succeeded against somebody who had failed.

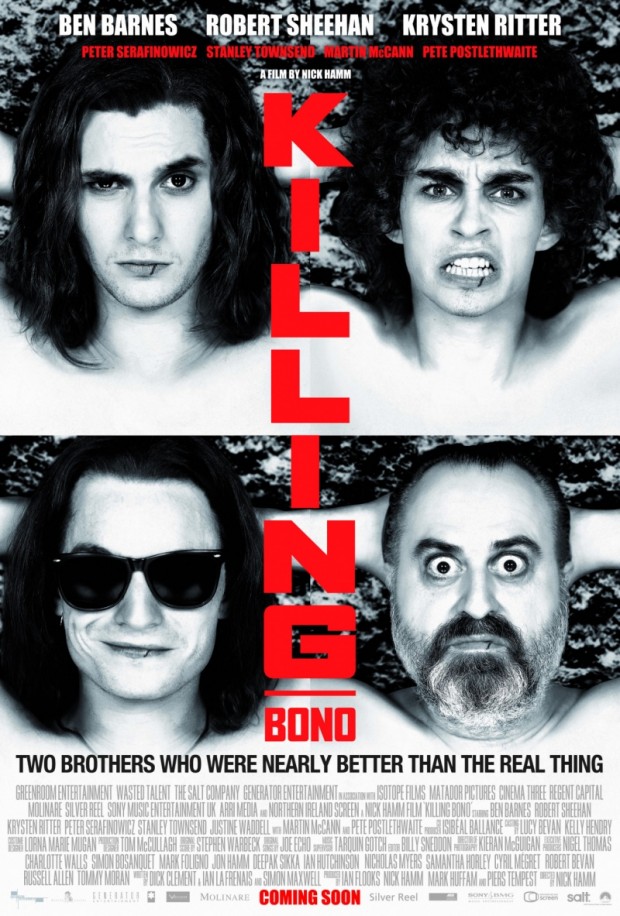

Killing Bono is on VOD and in limited release beginning this Friday, November 4th.