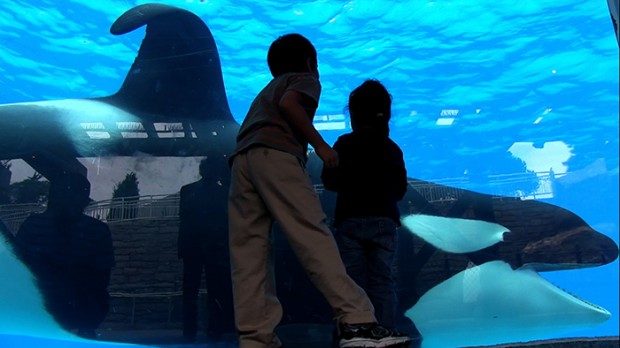

I’ve been to SeaWorld. I was a kid and it’s what parents usually do when they have the opportunity. There’s little doubt that it is a fascinating place, but I recall absolutely nothing about the experience, which means it was, in my mind, a happy one. But there is something bad going on under the surface of the water in the tanks of the SeaWorld Orcas. Captured in the documentary Blackfish, by director Gabriela Cowperthwaite, these seafaring mammals are living in harmful situations, causing an endlessly detrimental cycle.

In advance of the film’s nationwide showing on CNN this Thursday evening, I had the opportunity to speak with the director. Among the illuminating topics we covered was the fact that some might actually be turned off by the subject matter in advance of seeing the film, how she tried to keep the film from being gruesome yet still affecting, the ratio of male to female trainers, how she landed on the title of the documentary, and more. Enjoy our conversation below and I implore you to check out this wonderful documentary that is both a celebration of the Orca/trainer interaction and an unveiling of the way a corporation can pervert something so beautiful.

The Film Stage: I was talking with one of my friends about the film and she rescues dachshunds. She was saying that she’d love to see it but that it would just make her angry and upset. I’m curious about your reaction to the film already having that kind of impact and word of mouth, and it keeping people away from it because they are afraid of their own reaction.

Gabriela Cowperthwaite: Right. I think in a way, the people who might be upset… it sounds like your friend, who is doing really good work out there for animals, maybe she doesn’t need to see it. Maybe she gets it, right? Yet, the film, by design, I made it not necessarily graphic or gruesome. In fact, no, I won’t even say not necessarily — it’s not graphic nor gruesome. My seven-year-old kid saw it and we’re OK. So I think it’s palatable enough. But it’s content heavy. If you are someone who is entertaining the idea of taking your kids to SeaWorld, I think it’s important that you know what you would be seeing while you’re there. Make an informed decision.

From that standpoint, I’m curious if there were a lot of sequences of a gruesome nature that you did cut from the film?

Definitely. You hold back things as a director. You have to be smart about those decisions. You have to have an internal measuring stick as far as what is pushing it too far and turning people off. My idea was not to create a film that would tell you how to feel or what to think. I really wanted to create a fact-driven narrative. I think the facts and the truth are so powerful in and of themselves that people will get the message. You don’t have to scream it at them. That’s what I’ve learned. The measured tone that the film takes is what makes it so effective.

You’ve said that very early on you had reached out to SeaWorld about participating in this film. And right away, they were like, “Yeah! OK.” But they just never set anything up. And you mentioned that this is a tactic that corporations often do with something like this. That they show early participation, but then keep an arm’s distance to see what is actually being done with the project. How did you find out about this practice? Was it about SeaWorld specifically or was it about other corporations?

I think it was people who had worked at SeaWorld. I believe one of the former trainers who worked there told me. The moment that we started interviewing people who were going to be talking about things that SeaWorld has tried to keep under wraps for four decades, they would never weigh in. They’ve spent decades not having to argue against any of these truths. They’ve spent decades not even acknowledging any of that stuff had happened. It’s been successful for them to not argue against let alone acknowledge any dissent. So I think that’s where we meted out with them.

Throughout the film it’s noted this is a $2 billion industry. I’m curious if that is just SeaWorld or the aquatic life attractions worldwide?

It’s SeaWorld in general that is the $2 billion a year industry. Out of that, it’s been said that Shamu Stadium is roughly 60-70% of that.

Wow. OK.

When you go to SeaWorld, you’re going to see killer whales. You don’t leave that park without seeing a Shamu show.

The trainers you interview are going to be a smaller sample size because they’re the ones willing to speak out, but I noticed a good amount of them were female. Would you say it’s dominated by female trainers or more of a 50/50 split?

That’s a good question. I would say it’s roughly half and half. I would say that there were maybe more men in Shamu Stadium. There were certainly more men when they were swimming with killer whales. They’re no longer doing that. But the rocket hops, the spy hops and some of the more kinetic behaviors or kinetic tricks. I say kinetic behaviors like I work at SeaWorld. [laughs] Those are usually done by men. So I would say it’s roughly half and half.

I believe naming a film is almost half of the battle, especially with a documentary. A great title spreads and is easy to remember. This one is intriguing because most people don’t know the story of the Orca’s nickname way, way back as being “Blackfish.”Did you have multiple titles or did you hit on this one early on and stick with it?

Yeah. I had read a book early on called Orca: The Whale Called Killer that old time fishermen and native peoples to the Pacific Northwest area used to refer to them as blackfish; the moment I heard that, I knew that was the name. Especially since the first nation people, the natives, said that this was an animal that was never to be captured or harmed. It hit me and I never backed away from it. [laughs] I knew it was Blackfish, even though I’m not sure my whole team knew that was the name until much later. But I was sure.

Blackfish airs on CNN on Thursday, October 24th at 9pm ET.