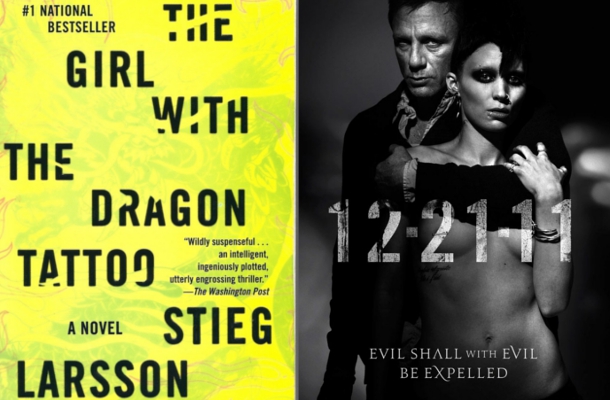

December 2011 has come and gone. The “feel-bad” movie of Christmas, writer Steven Zaillian & director David Fincher‘s The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, came in with ridiculously high expectations and a lot of scrutiny trained on it. Now, as the home release has arrived, it’s time to take a deeper look at the adaptation.

Swedish journalist, author and researcher Karl Stig-Erland “Stieg” Larsson died of a heart attack in 2004 at age 50, not living to see his Millenium trilogy of crime novels – The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo and it’s sequels The Girl Who Played With Fire and The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet’s Nest – first become international bestsellers and then an acclaimed film trilogy in Sweden. In 2008, Larsson was the world’s number-two bestselling writer, just behind The Kite Runner author Khaled Hosseini. In 2010, the trilogy’s final installment became the world’s most sold book.

Why did these stories become such a phenomenon? How does a novel with a plot that sounds like it was lifted from an Agatha Christie novel and then genetically spliced with a Nine Inch Nails album resonate on such a impressively international level? I cannot say for sure, but I think it has something to do with the underlying theme of the book and the films: this is a story about men who hate women.

In fact, that was the original Swedish title: Män som hatar kvinnor, or “Men Who Hate Women.” This dovetails with Larsson’s primary focus throughout most of his years as a journalist: exposing and taking down fascist groups in his native country. Larsson was a prominent journalist, and – like his crusading Mikael Blomkvist – co-editor of Ehe and an outspoken voice against both the ongoing fascist influence on the Swedish government and violence against women. He and his girlfriend Eva Gabrielsson were together for twenty years but never legally married. If their relations became public record, under Swedish law their personal address would be public information.

This legal nonsense probably continues up to this very second. Larsson’s girlfriend claims (credibly or not, are you a Swedish attorney? Then please email me, because the whole situation is revolting) that Stieg Larsson’s father and brother’s legal claim on the author’s work should be dissolved, since Larsson had nothing to do with them while he was alive. This epic-level legal f*ckery is preventing either a fourth book or both a fourth and fifth book featuring the same characters.

And who are these characters? Lisbeth Salander (Rooney Mara in David Fincher’s American version, Noomi Rapace in director Niels Arden Oplev‘s original) is a reclusive hacker, genius and ward of the Swedish state. She is hired to research Mikael Blomkvist (Daniel Craig, taking over the role from Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol villain Michael Nyqvist), a prominent, outspoken and fairly prick-ish journalist. Blomkvist has just been indicted of libel, sentenced to a hefty fine and (in the book and Swedish film at least), sentenced to a six month stretch in prison.

Blomkvist is hired by wealthy old Henrik Vanger (Christopher Plummer in the American film, and what a marvelous piece of casting genius.) Vanger, perhaps the only sane member of a sprawling clan of sociopaths, all of them members of the upper-crust of Swedish industrial-business society – has been haunted by the disappearance of his beloved niece some fifty years before. Since Blomkvist is currently a disgraced journalist who publicly resigned from his co-editor post at Millenium magazine, he has nothing to lose because he’s already lost it all. Duped by a heartless business magnate named Wennerstrom into publishing slanderous accounts of shady deals, Blomkvist is a crusader at heart who frequently leaps before he looks.

He is aided by his lover and Millenium co-editor, Erika Berger (Robin Wright), a married journalist whose husband shares her with Blomkvist in what is apparently a peaceful three-way that has been going on for years. (The relationship ruined his marriage, but not hers.) The American film wisely expanded Berger’s role from the nominal presence in the Swedish film to something closer to the pivotal role she will ultimately play in next two films. This relationship quite likely closely reflected Larsson’s own personal life, with the dynamic never quite underlined, but always present.

Plummer lends a needed gravity to a role that will become the moral center of an ever-sprawling über-tale of corruption, scandal, child abuse and depravity, embodied in the character of Lisbeth Salander. She drives a dildo up the ass of the repulsive social worker who has complete control over her life, despite the fact that she’s brilliant at her job and an adult woman. He raped her, after all, taking advantage of a social justice system that favors amoral monsters over any patient sucker who plays by the rules.

The scene is brutal in the book. The Swedish film and American film are both unrelenting – it’s one of the stark, mad and hideous moments which prove that David Fincher was the right choice to direct the film. Personally, I’d give David Cronenberg or David Lynch the job – and Fincher’s third on the list. I found myself wondering why the scene was given such a stark rendering in both book and film. Why give you such a queasy, vibrating sensation in regions you kind of wished no one had reminded you of while watching a story of deeply-embedded corruption within a wealthy Swedish family? In the end, the unrelenting quality actually isn’t the point.

The point of the Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, (beyond never, ever, underestimating pretty much any woman you ever meet for the rest of your sad little single-dude life) echoes from the book’s original title. Men who hate women – who hurt women, over and over again, unrepentantly and with savage, insane glee – will eventually be hunted down and paid back for their crimes. (Salander not only catches her rapist in the act on video but breaks into his apartment and tattoos the phrase ‘I am a rapist pig’ across his chest.)

This major theme is powerful enough to sustain the changes made in Fincher and screenwriter Steven Zaillian‘s American version. There are a number of minor changes between this and the Swedish film – the ending being the most notable. Zaillain’s script is actually far closer to the book than the original film, and while I half-expected Fincher to transplant the story to, say, his native California Bay Area (I could see the Vanger family lording over some misty island off the coast of Marin County), the second and third novels in the series are so firmly grounded in Sweden’s recent history that this would have been problematic.

The films and books all add up to a fascinating potboiler… as well as (inadvertently, maybe) an interesting case study in the divergent perception of sexuality between America and Europe. It’s no secret that American censors are a prudish lot, with that Puritanical streak still hopelessly prevalent. I’m surprised so much raw and brutal sex in Fincher’s film actually made it to the screen.

The first sex scene between Salander and Blomkvist exposes how different the European filmmakers view the sexual relationship. In the Swedish film, Salander finally comes to Blomkvist in the night after days spent sleeping apart in a cabin on Vanger’s property. In the book and film, Salander is seen sleeping with a girlfriend and thus is nominally “bisexual,” although she never labels herself as such or really considers her sexuality worth thinking about much at all. The sex scene in the Swedish film closely mirrors the hesitant quality of Salander – she does not open up easily, if at all. Her first tryst with Blomkvist is more of a release, and there is an animal-like urgency to it. It’s over just as quick as it started.

Fincher’s version of the same scene is much more straightforward. Blomkvist has just been shot at by some unknown assailant and returns to the cabin shaken and bloody. Salander tends to his wounds before stripping down and basically mounting him. It’s not exactly out of character for Mara’s interpretation of Salander, but it’s not exactly completely plausible. Their robust sexual relationship is given a fair amount of screen time, but it felt to me more like the pressure of the studio to streamline this aspect of the material. Americans are generally uncomfortable with any kind of overt sexuality on the silver screen, and if said sex colors outside their defined lines? Not having it.

Still, Fincher’s ending is nearly identical to the book’s: Salander has purchased an expensive jacket for Blomkvist, and waits outside his home. Such a gift is so out of character for the introverted hacker that when she spies Blomkvist and Berger warmly heading for his apartment – the two are clearly going to screw – she angrily trashes the jacket and rides away, deeply stung. Maybe Fincher’s more tender and American rendering of her sexuality highlights the woman-scorned ending… but if the next installments pull certain punches like this one arguably did, it will undermine the trilogy’s dark and urgent lessons.

Have you read the Millenium Trilogy? Did you prefer the Swedish or American film?