Not unlike Camerman, the documentary about accomplished cinematographer Jack Cardiff, Martin Scorsese’s A Letter To Elia, an hour-long half docu-ography/half diary entry regarding the life and movies of Elia Kazan, is a movie for strictly film festivals and the DVD collections of those that regularly attend film festivals.

The doc, written and directed by Scorsese and Kent Jones (writer for The Daily Show), doesn’t tell us anything new about Kazan’s highly-debated Black List days or how he felt about them (he’s recorded calling it the choice between two impossible choices) or even the trajectory of his film career. Instead, it offers a passionate look at the man’s canon from an equally immortal filmmaker and admirer.

Scorsese talks for the majority of the doc, and when the camera’s on him he speaks directly into the audience. The filmmaker speaks over dozens of clips from Kazan’s movies, from A Tree Grows In Brooklyn to America, America. A significant amount of time is spent on On the Waterfront and East of Eden, Scorsese explaining how the brotherly conflict between Cal and Aaron in the latter film dug deep into a psyche a 12-year old Scorsese couldn’t fully grasp while watching. That didn’t stop him, however. “I stalked the picture,” Scorsese recalls. “I followed it from theater to theater, across the city.”

These little bits are worth a watch for film lovers, but few else.

Tuesday After Christmas, on the other hand, does infinitely more with what is essentially one long clip: the downfall of a marriage. Another staple of the blossoming Romanian New Wave, Radu Muntean‘s film runs along the same line as The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, avoiding the politics of something like 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days and instead finding the comedy in an incredibly dramatic situation. Paul (Mimi Branescu) is a husband and father with a mistress, named Raluca (Maria Popistasu), on the side. Over the Christmas holiday, he must come to terms with his infidelity.

Thankfully, it is no where near as bland as the synopsis sounds. Shot in primarily master shots, Muntean’s eye judges no one. Cinematographer Tudor Lucaciu‘s lives around the characters, a silent observer. Branescu gives a deceivingly grounded performance, while Popistasu does a whole lot with not too much. Her best scene is the one that opens the film, consisting of one shot for 6 minutes, full of the post-sex banter a cute, unmarried couple comes up with. The compliments peak with Mirela Oprisor, however, as Paul’s scorned wife. Any reservations about her importance to the story go out the window in one long, pivotal, brutal scene halfway through. It says everything Clive Owen and Julia Roberts say during their brutal battle in Closer, only without saying it at all.

Not unlike a Kelly Reichardt film (Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, the upcoming Meek’s Cutoff), Tuesday After Christmas doesn’t seem to say much of anything. Yet I haven’t stopped thinking about it since the end of the screening.

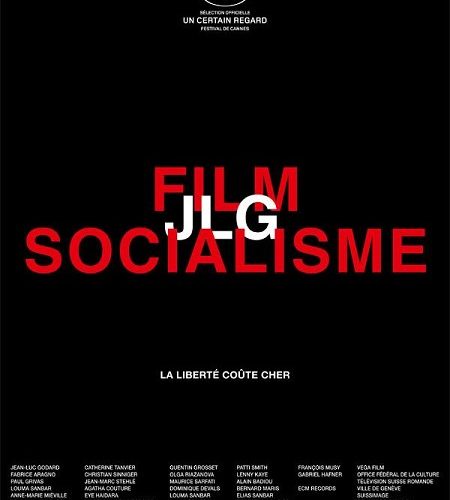

Jean-Luc Godard‘s new film, Film Socialisme, might just be the opposite. A flicker film on top of a narrative (?) on top of a documentary, Godard seems to say so much that, well, he doesn’t seem to say anything at all. And whatever is said is only half-heard, or rather, read by those who don’t speak German and French. Godard provides American viewers with subtitles he calls “Navajo,” which is to say he offers about half of what is being said. A noun, maybe a verb. Only a handful of prepositions for every delivered line.

Above all else, the film is frustrating. It lacks most of the awkward, socially-observant comedy present in the work that defined the director’s heyday, such as Breathless or Bande a part. This older Frenchman is much more angry and cynical than the once-film critic who helped set fire to a cinematic revolution 55 years ago.

Much of the beginning takes place on a cruise ship, where a brother and sister struggle with their childhood memories and confront their parents accordingly. This leads to conversations on everything from freedom to equal rights to family values. It’s all as general as it sounds. The frame is constantly interrupted by ear-piercingly loud, unbelievably poor audio complimented by pixalated digital video of a cruise party. From hell, it feels like. Gaspar Noe would be proud. It’s the kind of controversial material that’ll keep people talking. Some will like it just because so many hate it, and vice versa.

And, to be fair, what’s on screen is mostly interesting. But, also, mostly futile. Godard is no idiot, but what he’s saying is full of sound and fury, signifying not much at all anymore.

What are you excited for at NYFF? What do you plan to see?