Halfway through Dominga Sotomayor’s movingly tender coming-of-age tale Too Late to Die Young (Tarde Para Morir Joven), my mind jolted back to a movie I saw and instantly fell for a couple of months prior, Carla Simón’s Summer 1993. It took me a while to figure out why. Summer 1993 is set in early 1990s Catalunya; Sotomayor’s takes place at the decade’s outset, but on the opposite side of the world: a commune nestled in the arid cordillera towering above Chile’s capital, Santiago. Yet at some fundamental level, the two films speak the same language. Underlying Sotomayor’s follow-up to her 2012 feature debut and Rotterdam Tiger Award winner Thursday Till Sunday is a deep-seated nostalgia – the same longing for a long-gone era that rang achingly true in Summer 1993.

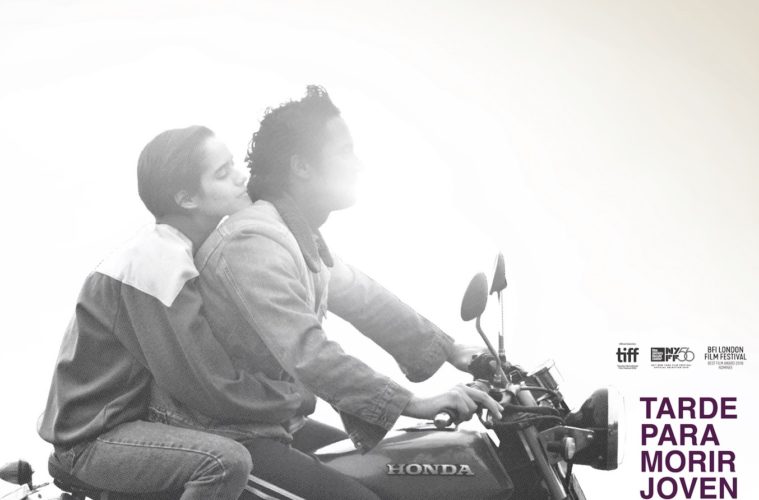

Inspired by the 33-year-old director’s childhood in the Ecological Community of Peñalolén – an environmentally friendly and self-sufficient commune founded some thirty years ago atop the hills surrounding Santiago – Too Late to Die Young is a multi-character canvas with a 16-year-old teenager as its focal point, Sofía (a brilliant Demian Hernández). Short-haired, pensive, and perpetually chain-smoking, Sotomayor follows the teenager as she navigates a period of profound changes. Away from school for the Christmas holidays and bracing for a big New Year’s party at the commune, Sofía spends her days running after a neighbor biker, grieving for her unrequited love over Sinéad O’Connor’s greatest hits, unleashing her teenage angst on her father, and fantasizing of leaving the commune with her mother – whom she hasn’t heard from in ages, but has promised to show up for the end of year’s celebrations.

Whether or not you choose to look at Sofía as Sotomayor’s cinematic alter-ego, the girl’s spasmodic need to dig up memories of her mother echoes the same endearing nostalgia that transpires from Sotomayor’s directing and writing. In one achingly melancholic scene, Sofía spends a night listening to old tapes of her mother’s voice, and frantically switches from one tape to another in an effort to patch sounds and memories together. Too Late to Die Young works in a similar fashion. More an episodic tale than a rigidly structured three-act plot, it is an act of recollection, and it unfolds the way memory does: as a series of hazy vignettes, more often than not unconnected to one another. There are moments when we follow Sofía’s driving lessons, others when she captures the kids hanging by the commune’s artificial pool, and others still when she trails behind the adults as they struggle to keep the village alive amid fires and droughts. Take it as an ethnography, and Too Late to Die Young offers a piercing and faithful portrait of three distinct demographics – the world of the grownups, the teenagers Sofía belongs to, and the pack of 8 to 10 year-olds hopping from one tree branch to another.

That all three cohorts are filled with complex, intricate characters speaks volumes of Sotomayor’s perceptive writing. The adults are far less proficient in life than one would expect, and it is up to the kids to step up and lead the way whenever the grownups get sidetracked by quarrels, alcohol-filled drama, or endless community debates. There are moments when the members of the youngest batch – especially the 10-year-old Carla (a scene stealer Magdalena Tótoro) – remind one of the wonder kid in Sean Baker’s The Florida Project, Moonee. Sure, there’s plenty of time to play, and plenty more to get bored, but lingering above the commune is a struggle for survival, a sense that nothing – not even the most basic necessities – can ever be taken for granted. Living exposed to troubles that kids their age would be conveniently shielded from, Carla and friends grow fast, and walk the commune with an irresistible no-nonsense swagger. “You’re too little to smoke,” Sofía shushes Carla when she asks for a cigarette. “Only on the outside,” the kid replies.

“In 1990, Chile itself was entering its own adolescence,” Sotomayor told me as we spoke after the feature’s world premiere at the 71st Locarno Film Festival, and the teenage angst afflicting Sofía mirrors the country’s post-Pinochet transition: a window of time where the power structures set up by the regime could be finally shattered, but never truly were. Perceptively, the mix of hope and anxieties permeating the commune serves as an allegory that stretches far beyond the cordillera. Political commentaries abound all throughout Too Late to Die Young, but Sotomayor parcels them out with jaw-dropping subtlety. When one of the poorer members of the commune agrees to help a wealthier household rescue their dog – allegedly “stolen” by a low-income family living outside the community – the division between the utopic hippie paradise and the inequalities of post-Pinochet Chile come to light with disturbing clarity.

Yet even when Sotomayor’s social critique feels more explicit, the narration never takes on a heavy-handed tone. The world of flickering lights and high-rises hanging below Santiago’s skies remains an altogether separate universe from the arid and dusty land populated by Sofía and the other commune denizens. If that liminal, anachronistic oasis feels so inexplicably close, credit goes to Inti Brione’s cinematography, playing with a low-saturated palette that adds to an intimate old postcard look to Sofia’s coming of age. And if Sofía’s quest to break free from a world she no longer recognizes as her own rings so true, if the look in her eyes as she listens to her mother’s voice feels so heart-wrenching, it is because Sotomayor’s work possesses a sense of authenticity that only deeply autobiographical features bestow. Memoirs are personal by definition – only a few, however, manage to speak with such a universal, instantly relatable voice.

Too Late to Die Young premiered at the 2018 Locarno Film Festival and opens on May 31.