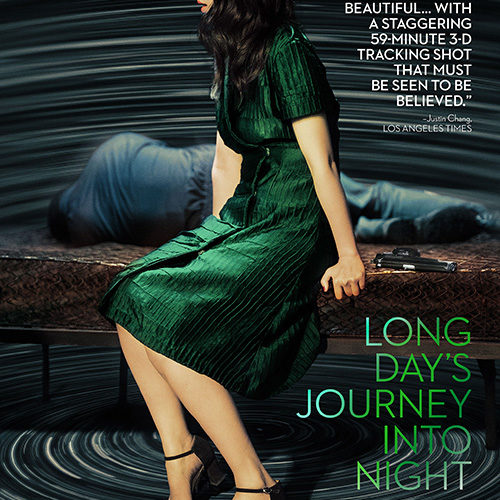

Bi Gan’s debut feature, Kaili Blues, proved one of the big critical hits of the last few years – all the more impressive for the fact that the writer-director shot it at the age of 25. His eagerly anticipated follow-up, Long Day’s Journey Into Night (no apparent relation to Eugene O’Neill’s play), represents a remake of sorts, returning to Bi’s hometown of Kaili in southern China to follow another man’s quest to find the woman he loves.

Along with narrative parallels, much of the same symbolism reappears – clocks abound – and the film is very similar even on a structural level, with a monumental single take running over most of the second half. Although Long Day’s Journey is a far more polished work than Kaili Blues, it also feels a lot more calculated, often sacrificing emotional impact for ostentation.

Journey‘s opening half, steeped in a ravishing neo-noir aesthetic, owes a big debt to Wong Kar-wai, especially In the Mood For Love, aiming for a similarly heady atmosphere of romance, nostalgia, and regret. The storytelling is wilfully opaque and, judging from the numerous walk-outs during the press screening I attended, will prove a challenge for many. By jumping back and forth across time via cuts with very little signposting, and often including magical realist touches – a waterfall starts pouring out of a concrete wall, a woman walks on the surface of a swimming pool – Bi creates an oneiric mood that never lets us know for certain whether what we’re witnessing is happening, has happened, or is all in the mind of the protagonist, Luo Hongwu (Huang Jue).

It’s initially frustrating to have very little idea of who the characters are or how they relate to one another. We’re told of the murder of someone called Wildcat, Luo carries a green book that is somehow significant, he’s often in the company of gorgeous women, and at one point he’s tortured by a gangster, but it takes too long for these disparate elements to coalesce into a narrative. It’s a waste to spend so much time trying to figure out what is actually a relatively simple plot: many years earlier, Luo had fallen in love with Wan Qiwen (Tang Wei), the girlfriend of a local crime boss with whom he had an affair that culminated in an event which forced him to flee Kaili, losing Wan in the process. It was only once the story comes together that Bi’s structural experimentation started paying off for me, and it was wonderful to let go and allow the bewitching images to transport me across layers of time, memory, and dream.

The sequence shot that closes Long Day’s Journey, however, took me right back out. Across 50-plus minutes, the camera comes out from the bottom of a mine, crosses a valley by cable car, flies down from a mountain on a drone, and ends up in the middle of an outdoor festival in full swing. A series of complicated, impeccably timed events occur along the way, many of which seem to defy the laws of physics. Oh, and it’s all rendered in 3D. The bravura is so over-the-top that it ends up derailing the film’s thematic and emotional trajectory. Rather than accompany Luo on his phantasmagorical journey, I spent the entire time trying to figure the shot’s seemingly impossible logistics and checking for hidden cuts. It’s an astounding piece of filmmaking — that’s beyond question — but also a prime example of where less would have been more.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens on April 12. Find more of our festival coverage here.