What Kiarostami is to the front seats of a car and Bresson is to the prison, so Aki Kaurismäki is to the perennial mid-80s Helsinki; that dark pastel-colored nowhere where everyone smokes and drinks and wears cheap suits. One of the many interesting things about The Other Side of Hope — a poignantly contemporaneous deadpan comedy which is surely amongst the greatest of his 20-or-so features — is that the auteur plants a Syrian refugee named Khaled (Sherwan Haji) into the center of that backwards world, as if he were a walking anachronism.

It’s a wonderful central conceit from the master filmmaker, a director who has spent a career simultaneously championing and poking fun at working class Finnish life — the fundamental melancholy of it, the want for escape and the booze. Here we’re asked to consider why a man who has just fled a war-torn country — and ended up in a wealthy western nation — still manages to look as if he’s come back in a time machine. Is it, perhaps, an oblique way of suggesting there are things we all can learn from these people instead of looking on them with pity? It might just be. Indeed, Hope is as contemporary and vital a film as you’re likely to find in 2017, but it’s also one of the funniest and most classically (not to mention beautifully) cinematic too. Shot on gorgeous 35mm by his enduring cinematographer Timo Salminen, it’s as cleverly detailed, as it is visually stunning and right from the very beginning.

We first meet Khaled in one such moment of virtuosity, as he emerges like Lazarus from a pile of coal in the hull of a container ship. He’s just smuggled his way in unbeknownst to Helsinki and — being the earnest guy that he is — he heads straight to the police station to register as an asylum seeker. He’s allowed to make his case and is processed by the system with dignity but, nevertheless, finds himself an eventual victim of the “alien act,” sitting in a half-way home (watching bomb reports come in from Syria) awaiting a perilous deportation to Turkey. Meanwhile, in a parallel story arc, a businessman named Wikström (played by Sakari Kuosmanen) leaves his wife, sells some shirts to a clothing store, multiplies his money in a high-stakes poker game — perhaps the film’s best sequence — and uses the winnings to buy a restaurant called The Golden Point (as you might have guessed, with more than a hint of irony).

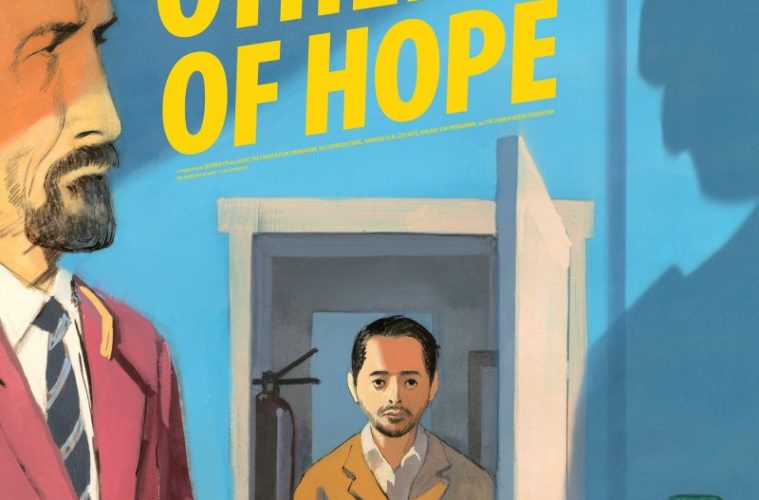

If you’re not familiar with Kaurismäki’s work, one might still recognize Wikström character as the sort of hard-edged, but loving father figure Wes Anderson (a spiritual descendent of Kaurismäki) tends to use in his films. He’ll knock you out if he has to, but he’ll respect you for taking the hit just the same. He meets Khaled by the dumpsters outside his restaurant and has just such an altercation, even offering him some work once he’s come to. Khaled’s broken out of the deportation office so Wikström pays him in cash and gives him a room.

In doing so Khaled becomes a member of the film’s central comic troupe, alongside a greasy host who attempts to turn the place into a sushi joint (complete with salted kippers and tennis ball scoops of wasabi); a disinterested straight-talking waitress; and a deadpan chef who could’ve been played by Buster Keaton. The opening night of service could have easily been lifted from one of the silent star’s earlier films and the cinephilic touchstones don’t stop there. Indeed, there’s plenty of Ozu in Salminen’s gorgeous head-on close ups; or echoes of La Nouvelle Vague in the editing; or even Fassbinder in the films staging and lush color scheme. One might just think of Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising when a leather-clad Finnish nationalist pulls a flick knife on our unlucky hero. The man and his cronies have been antagonizing Khaled throughout the film and serve as a reminder of the more unsettling things that await people like Khaled if they’re lucky enough to even make it here.

The knowledge that Khaled was separated from his sister at the Turkish border looms over the comedy of Kaurismäki’s film and we await news of her whereabouts from his Iraqi friend (apparently the only man in Helsinki with a mobile phone). Khaled’s made it to the other side of hope, it seems, but would happily give his life to have her safe and prosperous too.

This is why we genuinely need the great misanthropes of cinema. People like Kaurismäki, Haneke, and von Trier, amongst others, might try, on the surface, to feign a certain resistance to humanism and yet their kind seem to be the only ones capable of delivering something as vital as this. It’s a film that talks about hope without pretension, while maintaining a defiant faith in human decency — not to mention the faith that cinema itself still has the ability to translate that decency, with humor and clarity, to the screen. The Other Side of Hope does exactly that, brilliantly.

The Other Side of Hope premiered at Berlin Film Festival and opens on December 1.