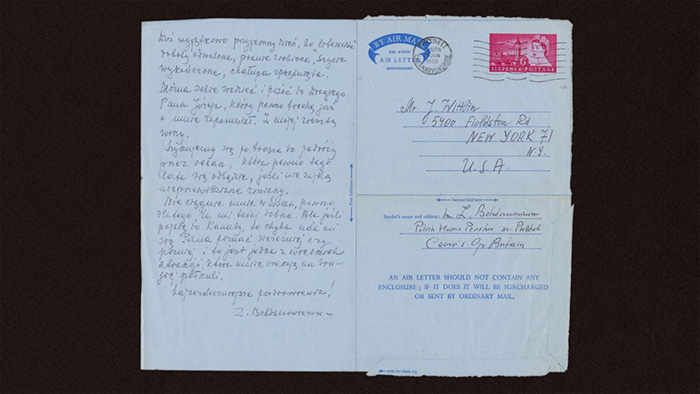

Director Sofia Bohdanowicz found a series of letters written between 1957 and 1964 by her great-grandmother Zofia Bohdanowiczowa (a poet) to the Nobel Prize-nominated author Józef Wittlin at Harvard’s Houghton Library. Both literary figures were forced to leave Poland during World War II with the former heading to Wales and the latter New York City. Zofia would eventually cross the Atlantic into Toronto, the newfound proximity allowing them to finally meet after so much correspondence. You truly get an insight into their minds after being victimized by such a horrible genocide as well as the unwitting loss of freedom their being driven from their homes created. Beyond that priceless personal content, however, Bohdanowicz and filmmaking partner Deragh Campbell also saw the letters’ objective tactility and subjective potential.

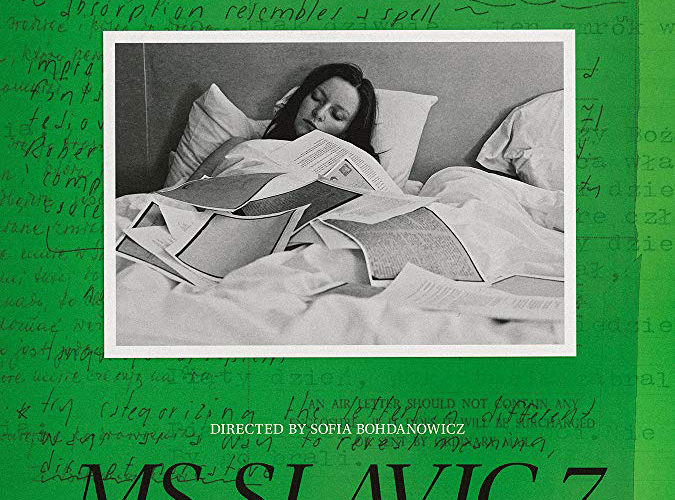

The result is the meta-narrative MS Slavic 7 (titled after the collection code housing the works). Campbell plays Audrey Benac, a character these two filmmakers brought to life in two previous films already. She’s rendered as a stand-in for Bohdanowicz with Zofia becoming her fictional great-grandmother. Rather than having the act of research lead Audrey to those letters, they’ve made her the new literary executor of the poet’s estate instead. The position shows her that there might be interest in Zofia’s legacy, the kind that an exhaustive exhibition could satiate after watching her art collect dust for so many years. These messages could very well be the project’s cornerstone being that they were written at such an indelible moment in her life. They could provide crucial historical information.

What does this journey entail? There’s the mundanely rote maneuvers of finding a hotel, making coffee, and entering Harvard with the intent to set her eyes upon the physical memos. There’s the quietly meticulous note taking and objectification of the artifacts themselves as well as the interpretive analysis of what’s read and touched behind closed doors. Before all that, though, is the unsurprisingly arduous process of actually knowing where they reside in the first place. So Bohdanowicz and Campbell structure their film as a three-day cycle of events moving from process-oriented actions to intellectualization to a flashbacked encounter with Audrey’s Aunt Ania (Elizabeth Rucker) that transitions from difficult to impossible. The first two-thirds of each day present artistic merit while the last third supplies petty familial politics.

Those first two-thirds also lend a quasi-documentary feel with Campbell experiencing the letters for the first time through the lens of Audrey. We’re watching her handle them with the delicacy forced upon her by an archivist doctrine and the intrigue of a researcher delving into a treasure trove of the unknown. Bohdanowicz moves from Audrey at the desk to static frames of the letters themselves with high-resolution clarity and the occasional textual subtitle. These moments are silent save ambient noise (as much of the whole is save those interludes blaring Johann Sebastian Bach), the experience of being in that room brought into the theater itself. The analytical monologues spanning emotional impact and the almost detached physicality of the materials themselves then follow, each born straight from those sessions.

It’s only the flashbacks then that remind us we’re watching a fictionalized drama. This is before the letters claim their autonomy to exist as documents and thus still merely an abstract extension of ownership. Questions of who can claim them are brought to the surface on sentimental and legal grounds. Does Ania have a stronger case because of age, proximity, and accessibility? Or does Audrey being that her grandmother willed her the executor status of Zofia’s literature? When one desires to let the art be housed by an impartial third party for the world to see privately (if they even know it’s available to be seen) and the other seeks control to place a much wider public spotlight upon it, the answers to these queries become critical.

What’s interesting about the film itself, however, isn’t whether or not they’re asked or answered. The dramatic and philosophical ruminations stemming from the work within the work is fascinating and Bohdanowicz using this lens to expose it is a unique solution, but it’s just one layer. While that takes center stage for a good four/fifths of the sixty-minute runtime, the last fifth turns our attention squarely onto Audrey. No longer is she merely our entry-point into an academic endeavor. From out of nowhere she suddenly becomes the true star with impulses moving beyond the art. Where objectivity used to rule the day, one cut to a bed colors everything in a new light. So attuned to letters from the past, we’ve forgotten the actual life being lived today.

Is it enough to vault MS Slavic 7 above its initial utility? Maybe. Those uninterested in cinema’s experimental and formal qualities probably won’t find themselves sitting down to be disappointed or bored by its very insular nature anyway. So those seeking it out will be the ones with the desire to embrace its unorthodox narrative style and subtle progressions. The dramatic scenes between Audrey and Ania are often too broadly performed to not stick out when compared to the otherwise sedate pacing and aesthetic, but they do earn that jolt by proving important enough to overshadow the rest. These two women ultimately turn Zofia’s legacy into a product and thus commoditize their ancestry. They make it so those letters possess meaning through literalism, artistic intent, and posthumous value.

MS Slavic 7 premiered at the Berlin Film Festival.

Follow our festival coverage here.