There was little hesitation when asked if I wanted to interview Rampart director Oren Moverman, his latest film with collaborator Woody Harrelson. Moverman is the same man that graced us with a criminally underseen The Messenger starring Ben Foster and Woody Harrelson as messengers of doom to the families of combat soldiers lost in America’s current war.

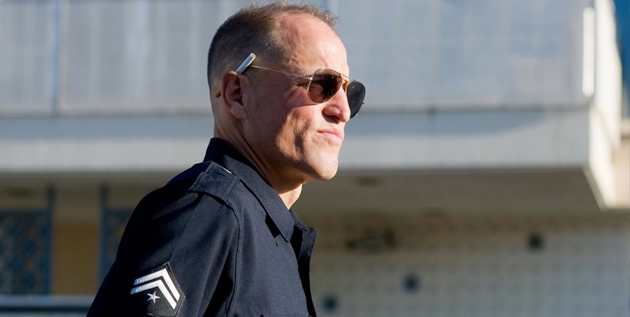

Rampart is a bit of an about-face and focuses on Harrelson as a corrupt police officer embroiled in the Rampart scandal in the LAPD. While talking with Moverman we discussed Harrelson’s initial negative reaction to the film, preparation for a role, the vastly different cinematographic methods used within, and the freewheeling nature of the way he shoots.

The Film Stage: [Woody] Harrelson went through some serious training to get into this role. Do you encourage that? Is that something that you would do yourself if you were an actor?

The Film Stage: [Woody] Harrelson went through some serious training to get into this role. Do you encourage that? Is that something that you would do yourself if you were an actor?

Oren Moverman: Absolutely. I think it’s essential. The biggest part of the job, in my mind, because if you do prep; if you research the character; if you go deep into the real side of the life you’re portraying, then you can do anything with it. Then you are just in it. You are the character and the script could be what it is, but you could do complete scenes unscripted as the character. You just understand, inside out. I think that’s a very, very helpful tool in the way that we work, which is not completely improvised, but definitely left room for the actors to bring in more of their characters based on their knowledge of them. So what Woody did was immerse himself completely, and the world Dave Brown was walking through. Every time he showed up on set, he was Dave Brown.

It’s funny that because that was actually my next question. He talked about how the shoot lasted about 35 days. And he had one sequence where he’s sitting there, talking with his family [in the scene], and all of a sudden it expands from one page to eight pages. Do you cut out other scenes because you know you’re going to be crunched on time? Or do you make it work?

I think what you do is trust the process and really, really, really pray hard that it’s going to work. And trusting the process means that we know that not every scene that we’re shooting is going to make it into the film. And sometimes we’re even surprised by how many are not making it into the film. But those scenes exist in the film for us because they inform a lot of what’s in the scenes that are kept in the movie. That’s why I say that they are part of the process. It’s almost as if you’ve done other scenes in preparation for the scenes that take over. And I really do let certain scenes take over the movie.

There’s something that’s hard to explain when you’re on set where you start feeling the movie come together. It’s not the movie that’s in the script. It can’t be, because the script is a piece of paper with words on it and film is a visual medium. So it’s something that grows and you start recognizing as you shoot the movie and then you sculpt it at the end in editing. And that’s really what happened here. When we shot that scene that you’re talking about, which was a relatively short scene. It just kept growing, and growing, and the spaces that were in between the lines on the page were starting to reveal themselves. And clearly when you shoot a scene like that, and it’s eight minutes long, you know that something’s going to go. But like I said, you hope and pray that when you get to the editing room that you’ve made the right choices and that you can make those things work.

Talking about film as a visual medium, obviously the cinematography switches between a couple of styles. It’s steady at certain points and then in some intense sequences it almost looks like it’s hand-held. Was there ever a point where you wished in the editing room that you had stuck with one or the other? Or do you like the cohesion, or lack thereof, between those two difference styles?

Well, the film was designed to work this way. It may feel like either it’s organic or it’s slapped together, but the film was designed to have these particular looks for certain scenes and creating kind of different worlds and having them come together at the end. Trust me, as a director you wish a hundred things were different with every scene.

[Laughs]

Because you’re the one spending the most time with them and at a certain point you just wish there was something else. But if I have to be more objective, I really felt that when we got out of the production stage, we really had everything we needed to make the movie that ended up on the screen. It was a clash of different styles. It was a clash of different personalities in one guy. It was sort of an unhinged kind of exploration and had an unhinged kind of style to it. It was embracing Los Angeles visually but it was also kind of being oppressed by the visuals of LA, especially the intense kind of punishing sunlight. So it’s all these elements we talked about before shooting the movie that we kind of brought together. And then you find in the editing room the balance, hopefully, between all those things.

Obviously you co-wrote the movie with James Ellroy, who’s a very famous true crime writer. And a lot of his stuff ends up dealing with LA. I first want to ask how he got involved in the project and I also want to ask, in your opinion, what is it about LA police corruption that spawns so many films? Is it the proximity? Or is it the level of these events themselves?

Well, Ellroy actually wrote the original script. So I came in after him and worked with his material and shaped it and developed it. Ellroy’s a quintessential LA writer. He lives here. He’s very close to the police. He’s fascinated by crime stories. True crime and fiction. And because he’s a product of LA—he grew up here, went through a lot of personal events. Traumatizing events. Most famously his mother’s rape and murder. That puts him in a unique position to really go after these stories and really try to portray them from within. So that’s his personal obsession, I think. A lot of his books are centered around a narrative that is LA crime stories. For me, the narrative was a big part of it. An important part of it, but was not the absolute center of the movie. For me it was more a character study and I was amazed by the character that he had created. I wanted to really be in a privileged point of view where you’re spending so much time with the character and you’re in his head, a lot of it. You’ll hopefully be getting an experience that is different from your typical LAPD movie or a typical Ellroy movie, if there is such a thing.

How involved were you in the casting? And at any point did you stop and say, “this cast is HUGE”?

Oh, I was very involved in casting. Perhaps the biggest part of my job. It is huge. It was even bigger. But to me it was amazing because basically you have one character and then everybody else is a supporting role, and small ones. I mean, Steve Buscemi is in a scene and a half in the movie. Sigourney Weaver is in three or four scenes. It’s just that kind of spirit that created this momentum where a lot of these very, very talented, very, very experienced great actors were showing up for a few days to do their scenes. So I felt like I was getting a lesson like no other where every day I got to look through the eyes of different actors who had different styles and different approaches to the work and try to bring it all together. So it was nothing but fun for me.

Harrelson is the anchor-point for the film. How important was it to keep him firmly in focus during the film and was it, at any point, detrimental to some of the other excellent actors that you had where you had to cut down scenes or things of that nature?

Harrelson is the anchor-point for the film. How important was it to keep him firmly in focus during the film and was it, at any point, detrimental to some of the other excellent actors that you had where you had to cut down scenes or things of that nature?

Yeah, it was always going to be him. It was always going to be the focus on him. He is the movie. He is the state of mind in the movie. So really I was very up front with it with the other actors. Everybody knew this was Woody’s movie. This was Dave Brown’s movie and everybody plays a certain element of his life or a certain reflection of him. But it’s never going to be about them. With the slight exception of Brie Larson, because I felt like even though her character of the oldest daughter is not written as the center of the movie, and it’s not in the movie itself. But there seems to be because of a final scene where there’s a sort of good-bye scene he has with her, there seems to be a certain weight to her character that has a feeling of continuation of the movie that has to do with her, if that makes any sense. Because she’s the last person we see in the movie, I think she kind of lingers longer in our minds and kind of personifies the price that he paid with his family. But then again, that just illustrates the point that every single character is there to show something about Dave Brown. As opposed to themselves. It’s the Woody show.

It’s funny, because having such an integral actor in your film and you showed him a first cut of the film, a rough cut. And he has been vocal recently in interviews that he did not enjoy it. Then he saw it a second time. What was that process like to go through showing your main, lead actor what you have been working on in a way that isn’t finished? He said that he didn’t voice that opinion, but could you read between the lines and see it in his face?

Oh, yeah, yeah. [Laughs] Woody is not someone to filter his self. That’s one of the beauties of Woody. He says what he thinks. He’s not going to mix things pretty if they’re not in his mind. First thing I would say is that this happens a lot more than you realize. And actors don’t usually talk about it. So I applaud Woody for talking about it. But I know plenty of stories of actors who saw their movie and hated it. And even ended up supporting it in the press. But it’s a very, very fragile thing to appear in a movie and then watch yourself. It’s complicated. It’s hard. And on a movie like this, where Woody is in every scene of the movie and almost every frame of the movie, he is the movie, as I said. So, I think it was overwhelming. But also, and there’s a lesson here, it’s very dangerous to show a film that’s not finished… to anyone. Especially to your lead actor.

And let the record show that I thought it was a bad idea. [Laughs] I didn’t think he should see the movie before it was finished. He thought he should. And I defer to him because I respect him, so I showed him the movie and clearly he was not happy with it. He didn’t like it at all. It was very different from what he had in his mind. It was very different from the script, which he knew to expect, but still it’s overwhelming when you’re in it. And you know, it happens. The director goes off and spends a few months with the editor in a room and comes back and everyone’s still, in their head, they’re still shooting the movie. So it was a rough time, but you know, to his credit, we talked about it. We promised each other that this would not hurt our friendship if he never came around to liking the movie. I love the guy and I respect him and I respected his opinion, but I said, ‘Just watch it one more time. When it’s finished.’ And he agreed to. And when he did, he was amazing because he came to me and said, you know, as someone that doesn’t filter himself, he said, ‘I made a mistake. I’m sorry. Will you forgive me? I was wrong.’ And it takes a big man to say that and he’s that kind of guy.

You really have some unique experiences in your own life. [Editor’s note: Moverman was a former Israeli soldier] Did that work into this film or did you mainly work off of what was written and what was on the page?

I think it’s complete overlap. I don’t even realize when it happens, but I’m sure it’s there. And I think that it happens in the writing and then rewriting, and then the directing. There are elements of yourself that you put in everything. In this particular case, my relationship with Woody and Ben [Foster], we’re so close that I think we influence each other and we bring our lives together in our different experiences and out of that, things progress. It’s hard for me to point to it and say, ‘Oh, that’s my life’ or ‘That’s his life’. But it’s definitely in the process.

Can you give any updates about Terrorist Search Engine or Queer?

Terrorist Search Engine? I’m writing that so there’s no updates except that, you know, I’m not writing it right now because I’m talking to you. And then Queer, we’re trying to put the money together to shoot it this year. Steve [Buscemi]’s directing. It’s a project that’s been taking a long time to come together and one of my favorite scripts I’ve ever worked on and hopefully we’ll shoot it after he finishes the next season of Boardwalk Empire.

Rampart is now in limited release.