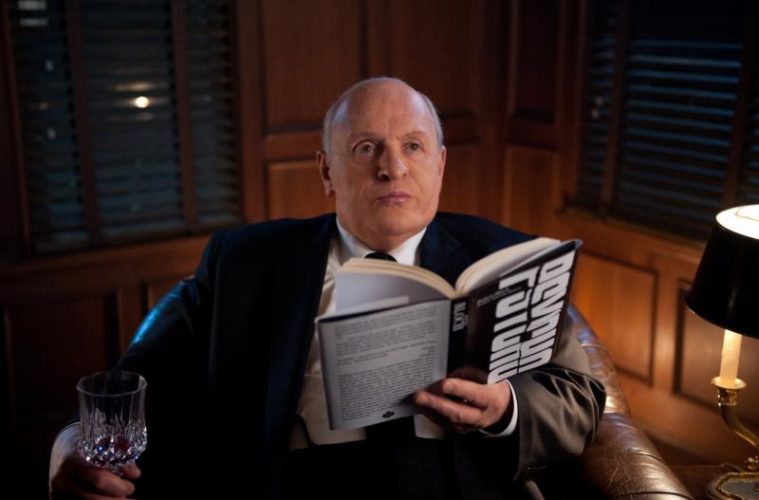

Last week I had the great pleasure to sit in on a roundtable discussion with Stephen Rebello, who wrote the novel Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, which inspired this upcoming biopic Hitchcock, from Anvil: The Story of Anvil director Sacha Gervasi. Together we discussed why Alma isn’t a bigger part in the book, revisionist people, what he thinks about the man versus the myth, how the director differs from Paul Thomas Anderson and David Fincher, and much more. Check out our conversation below regarding this new look at The Master of Suspense.

The Film Stage: So, why Hitchcock?

Stephen Rebello: Oh, gosh. Something’s wrong with me, I guess. I was always fascinated by him. He told me once that he cast actors in terms of architecture. Sometimes the structure of the actor’s face and their body would dictate the architecture of the set. Which I thought was fascinating because it was something I felt but I couldn’t articulate what I was feeling. It felt like those actors belonged in that world.

You previously said that you owe a great debt to Hitchcock personally, because you got the last interview with him.

It was pretty scary. But he wanted to see what people were made of. He played a stunt on me. I was made to sit in a specific chair in his outer office, and his secretary said that he was in with his barber for his daily shave and haircut. They opened the door just slightly to a scene of Hitchcock with his head tilted back and a straight-edge razor against his neck, and then slammed the door. A few minutes later he came in. But I was surprised that he cared enough to stage a prank for me. But he also did it to see if it would throw me. But it didn’t. I was delighted by it. Because that interview was published around the world, it elevated my career. That also introduced me to a lot of the Hitchcock inner circle, where I became entrenched and went on to make this book.

They say hindsight is always 20/20. The film makes a very obvious point that a lot of people doubted Hitchcock could pull Psycho off. So I’m curious, because people are revisionists, if you ran into people that were hesitant to admit they were doubtful of Hitchcock or were people very open about that?

I think it’s tough for people to admit that they were wrong. The real decision makers at Paramount were long gone by the time I wrote the book, sadly. I would have loved to heard how they might have spun that. But it was very clear from reading the telegrams to Hitchcock after the movie was making money hand over fist, and critics were hating it, yet Fox and Paramount only wanted to release it in two theaters. But the telegrams were all about, “Oh, we always knew you would do it!” “Another Hitchcock triumph!” These were the same people, and it wasn’t always those in the studios but those who were in his circle who left his circle because of Psycho. There was a wonderful subplot in the film of people in his circle who literally left Hitchcock because of how disgusted and repulsed they were by the very idea that he was going to touch this unclean property. And they all came back. Nobody knew but Hitchcock. Nobody knew but Robert Bloch, who is almost never given credit for creating Norman Bates and Mary, and Mother. All of these things. But he felt slighted by all the people who wrote it off: “Psycho is based on a short story.” “It all came from Hitchcock.” So, as I made a case in the book and hopefully it came through in the movie, success has many fathers but failure is always an orphan.

So now a lot of directors who maybe doubted if they could reinvent themselves can take inspiration.

Yeah, but everybody thinks they’re reinventing the wheel. Everybody thinks, “Well, you’ll be the one that can’t do it.” I don’t think that contemporary directors are as type-cast as Hitchcock was. Hitchcock really specialized in many genres but a lot of people think of him in one way. If you grew up a certain age, you think of him as a man who directed horror movies. I’m generalizing, of course. But if you’re of another age, you might think of him as a man with really glossy, elegant, romantic thrillers with beautiful people and people setting where nothing ever terrible happens to those people but you sweated it out during the course of the movie. There are many versions of Hitchcock. Whenever a journalist says to me, “You really nailed Hitchcock,” I’ll usually say, “Well, which Hitchcock do you know and how do you know him? Did you spend any time with him? Or what films did you see that informed that view?” He was many things to me. He was a chameleon. He felt he needed to go in another direction or, as the film says, nail him into a coffin and that was it. He was going to be that old guy that makes movies we know what to expect from. And good for him. But I don’t think David Fincher has that problem. He can do The Social Network, he can do Zodiac. They can go wherever they please. I mean, what’s a Paul Thomas Anderson movie? I mean, they’re great, to me, but they’re not the same movies. They’re challenging movies, every time. But I do wish there was a contemporary Hitchcock. I love showmen. I love that era of filmmakers. Whether it’s William Castle or [Cecil B.] DeMille or Hitchcock. People who are larger than life and almost as large as the movies they make.

This movie could actually be titled “Alfred and Alma.” She’s so front and center. But in your book, she’s really more of a peripheral character. Do you think her role in the success of Psycho and the making of Psycho was as great as the film implies?

The book, Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, was largely dependent on what the people around Hitchcock told me at the time about the making of that film. I apologize for downplaying Alma in that book because I was under a misconception. I was under the impression that most people knew how important she was to every one of his films. With the film, I wanted to correct that. So it was a course-correction on my part. There was another reason. I saw, literally in the shadows of Hitchcock, Alma watching him. Being very gracious with the crowd but I saw an enormously sharp woman. I felt that if you blindfolded her, she would know what everyone in the room was wearing, what was wrong with what they were wearing, and how she would redress them. Just enormously smart, and bird-like. Intuitive. A very observant person. She was accustomed to, and maybe even more comfortable with, being in the shadows. Except in the editing room. Except on set. Where she knew her stuff. She had spent years in film before him. He was beholden to her. He was almost on bended knee, in a sense.

Talk a little about the script.

The script was vetted by a lot of people and Hitchcock associates came to the set. Marshall Schlom, who was the script supervisor on Psycho, came in. That was a very big deal for a lot of us. He said, “Thank you for bringing to life the Hitchcock that I knew.” So I felt that we were kind of on the right track.

On the press notes it says that you were credited just on the book. But in terms in the overall screenplay, how much were you involved?

John McLaughlin wrote the first several drafts. He put down the template for the structure. John came up with the idea of using Ed Gein. Hitchcock needed someone to talk to and so that gives us a look at his mind and psyche. The notion of having the film start as a “Hitchcock Presents” and the structuring of that was his idea. But really, almost everyone in the film had input.

Hitchcock opens on Friday, November 23rd.